to the stars, but at a lethargic snail’s pace

Usually, considering the typical subject matter for this blog, it’s quite rare for me to say that a concept just isn’t really ambitious or aggressive enough. In fact, I usually tend to play either devil’s advocate or wet blanket with futuristic ideas, especially those of transhumanists and Singularitarians convinced that revolutionary gadgets so far extant only in comic books, are just around the corner thanks to “exponential technical progress.” But the members of the Tau Zero Foundation, who seek to build humanity’s first interstellar probe, seem perfectly content with taking entire centuries to complete their task, with one of their founding members going so far as to publish an extremely flawed paper predicting the first mission to another star only by the 2190s while a fellow founder warns us of how slowly the project will actually move on Discovery News. It’s as if they’re the anti-Singularitarians, which is absolutely befuddling given that their consultants are highly capable scientists and engineers with big dreams. As odd as it may sound coming from me, their proposed interstellar probe, a craft the size of a skyscraper intended to fly before the year 2200, just isn’t ambitious enough of a project.

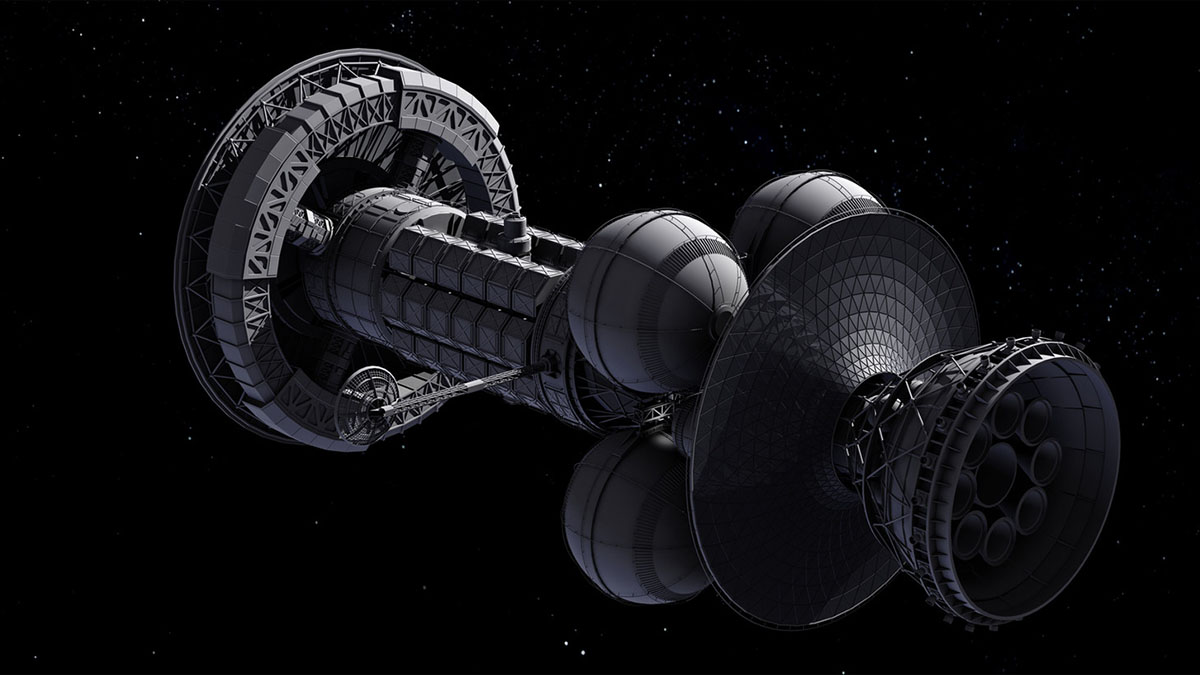

Yes, I know, spaceflight is a very complicated business and technology has to be tested, then retested before anything valuable or important actually goes into the payload container, and given the complexity of building a vehicle going into orbit or farther, means that months of fine-tuning need to go by between each test. And this is well before we get to any human-rated spacecraft, where everything must be triply redundant and vibrations in capsules that will be shaken by hundreds of thousands of gallons of burning fuel shot out of huge nozzles, must be reduced to a minimum. So you’d think that something like an aircraft carrier-sized fusion reactor that is the Tau Zero’s theoretical vehicle of choice, the Icarus, is probably going to take a little while to build and test, especially when we consider that nuclear fusion which yields more energy than we put in it is still a ways off and that we’ve never even tried to launch tens of thousand of tons into orbit, much less beyond. Giving the completed Icarus’ estimated weight of some 55,000 tons means that it would have to put out 44.7 EJ to reach escape velocity. That’s roughly 10% the amount of energy our entire world uses annually, to give you just a bit of perspective. How do you launch something that big and accelerate it to relativistic speeds? Building it in a relatively low orbit to give it a bit of an initial boost sounds like a good solution, but that would take millions of very expensive and dangerous human hours in orbit, countless robots, and thousands of launches with very large and heavy, or very delicate and expensive, components for the craft.

And the more we will approach this project by thinking about today’s capabilities, resigning ourselves to only a few incremental improvements over the years in what could be launched and for how much, hopefully adding up to a major gain in capability over the next century, the less likely it is that anyone would want to build Icarus in the first place. As noted in the previous link, a project intended to last some 80 to 90 years at best just isn’t viable for any space agency because it will utterly dominate its project roster and tie up its resources for a very long stretch of time, possibly longer than the agency will even exist. We can plan to accomplish something in the next decade or maybe even two at most, but beyond that we have to consider the impact of any future war, shift in government priorities, or diplomatic agreement that may adversely impact the craft’s construction. This means that Icarus would need to be assembled in just 15 to 20 years at most, and it would have to be faster than planned. Yes, that’s a very tall order when we’re talking about relativistic velocities and it poses dangers to the craft itself since high velocity impacts with interstellar debris are nothing to take lightly. However, when future mission planers are given plans for a craft that will take more than three times longer than their careers will last to complete its mission, and is intended to fly to a nearby star where we’re not sure we’ll find anything like planets, much less something as sensationally crucial to securing funding as alien life, they’re unlikely to be sold on the idea. They’ll probably just tear it to shreds with questions that have few good answers.

Ideally, if we were to find planets orbiting Alpha Centauri either capable of hosting life or having moons which could give rise to alien organisms, Icarus could well be greenlit because the mission could be done within a human’s career. Granted, it would have to be a long career, but those who built and launched the craft could still be around to advise new generations of engineers and scientists, and to see the first signals of a human craft coming from another solar system. Just to add to the project’s value and public relations impact, it might not be such a horrible idea to think about making Icarus a manned probe, though only for an ideal mission to our nearest stellar neighbor because a destination more than a few light years further would mean that we’d have to raise a new generation of astronauts in deep space to complete the mission, something we are not ready to do yet, especially considering how a generation ship changes the nature of the endeavor. However, without a target in our astronomical sandbox, it seems that traveling to the stars is something that will have to wait until we either master relativistic propulsion using something extreme like black hole reactors, or until a typical human has a nearly unlimited lifespan thanks to the kind of life extension that’s still science fiction. It’ll have to be driven by revolutionary technologies developed for a much more ambitious mission, or enabled by breakthrough technologies that Tau Zero very cautiously mentions and puts on a back burner. And it won’t be an extremely long term, conservative, step-by-step project of future space agencies willing to enlist two to four generations of engineers to a single project for which they would have to find trillions of dollars.