why we need to make fusion work with a new kind of reactor

Sustained nuclear fusion is one of those perpetually almost there ideas that we keep pursuing despite physics and budget slashing politicians fighting us every step of the way. Why? Because if we can make it work, we can pretty much abandon fossil fuels overnight and have the capability to scale energy production to match whatever needs we’ll have for centuries into the future with very little waste that will decay into harmless, inert matter within just a few decades rather than the millennia for fission byproducts. If we want to explore space and have an energy infrastructure that doesn’t involve a vast amount of dead plant matter being burned while giving off toxic fumes that cost developing economies over $5 trillion a year in healthcare costs and lost productivity, we’re going to need to master fusion. But before we have a net gain from our reactor prototypes, we need to tame the magnetic fields that control the flow of plasma that will induce and contain the reaction.

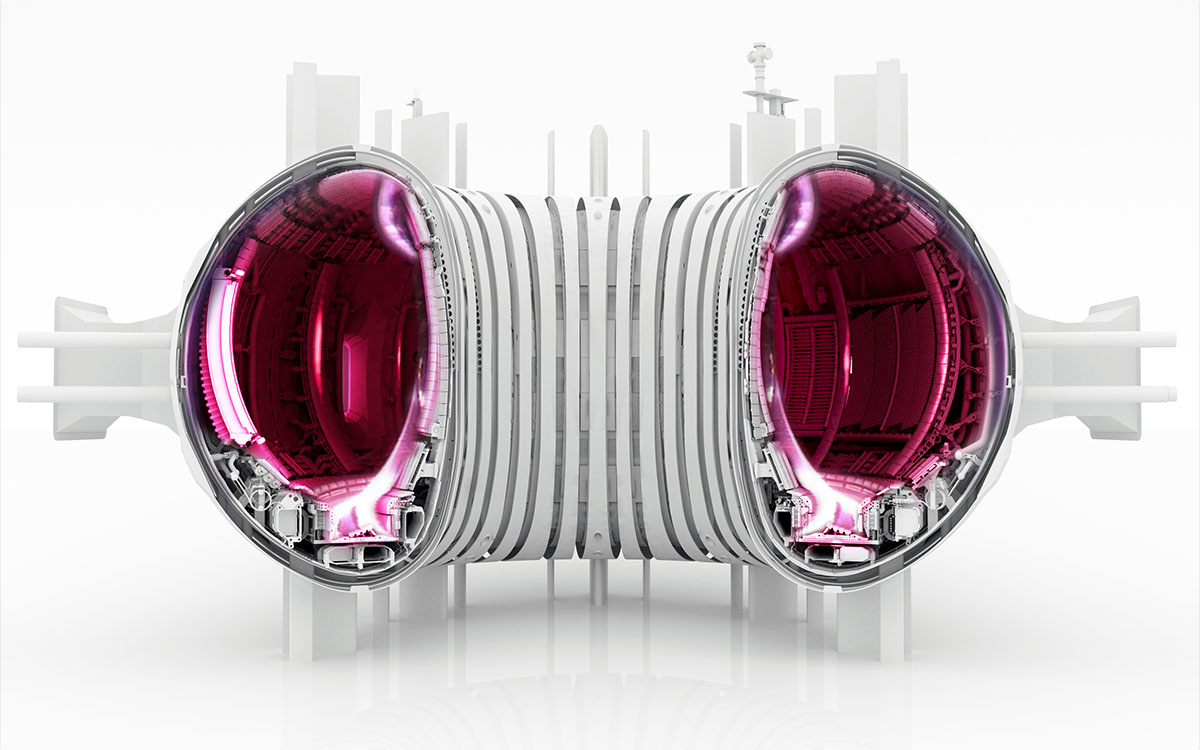

Over the last 60 years, researchers have tried many configurations and ways to ignite fusion to narrow down the optimal design and right now, the most promising type of reactor is the doughnut shaped tokamak where hydrogen gas is ignited with lasers and spun around the confinement chamber until it compresses and heats up to a target of 100 million °C, using heat to make up for the lack of gravity that would ordinarily help force atoms together. And today we can come quite close to this with a big caveat. Existing tokamaks can only keep the plasma flowing for six and a half minutes. To start seeing a net gain we need the reaction to last for half an hour, or 4.5 times longer, which is a tall order that requires a modification of the best existing design. Luckily, a new prototype in Germany seems to have a really good chance of making this happen by adding a literal twist to today’s tokamaks. Instead of just confining plasma, it forces it to flow along an extended Mobius strip to generate a magnetic field that can compress it to maintain fusion.

This design is called a stellerator, and it’s intended to use only its magnets to keep the plasma contained instead of electrical current, meaning that even a protracted interruption in its current is now irrelevant and the reaction can keep humming along. The Insane Clown Posse may not know how magnets work, but physicists do, and it’s pretty amazing what we can do with them. However, before we get too excited, we need to make sure that this design is producing the predicted fields and a recent preliminary test shows that the first stellarator matched theoretical predictions almost exactly. Its error rate was less than 1 in 100,000, which means that it should be sound as the tests ramp up towards the required 30 minutes of operation mark. It’s important to keep in mind that this reactor isn’t going to be viable for any real world power plants, it was built only to test the concept and it will take years until all the bugs are shaken out and we can start testing how much net energy a stellarator can produce. So it’s still going to be a long, slow road.

But at the same time, consider for just a moment that despite six decades of shoestring budgets, extremely disinterested politicians, and nay-saying from cynics, we’re marching closer and closer to viable fusion. This is what real science looks like. Slowly chipping away at a problem, tweaking design after design until we get one step closer to our goal. Stellerators might not be the end-all-be-all of fusion designs and require a lot of tweaks until they power your home, but they will be a success story of scientific persistence. And we should be encouraging more research into technologies like this, especially when we’re transitioning to a post-industrial world that relies on countless power-hungry machines to run and have an environment we have to restore and preserve if we want our species to keep going strong. Should this new design fail and researchers take the lessons they learn and come up with a new method of controlling plasma, we should see it as another step forward rather than complain about the lack of working reactors. Our future depends on helping science follow its course to figure out fusion.