and once again, biology puts up a fight…

Sometimes I can only sympathize with the kind of frustrating setbacks experienced by biologists. Whereas an entire area of STEM disciplines can rely on formulas and basic theory to get them at least close to where they need to be, biology seems to change its mind on a dime, and what seem like very straightforward and simple ideas can end up grinding to a screeching halt when scaled up beyond a few cells. From promising research into greatly increasing lifespan to countless potential cancer therapies, some of the failed efforts by biologists make me wonder if working in the discipline ever feels like battling Murphy’s Law.

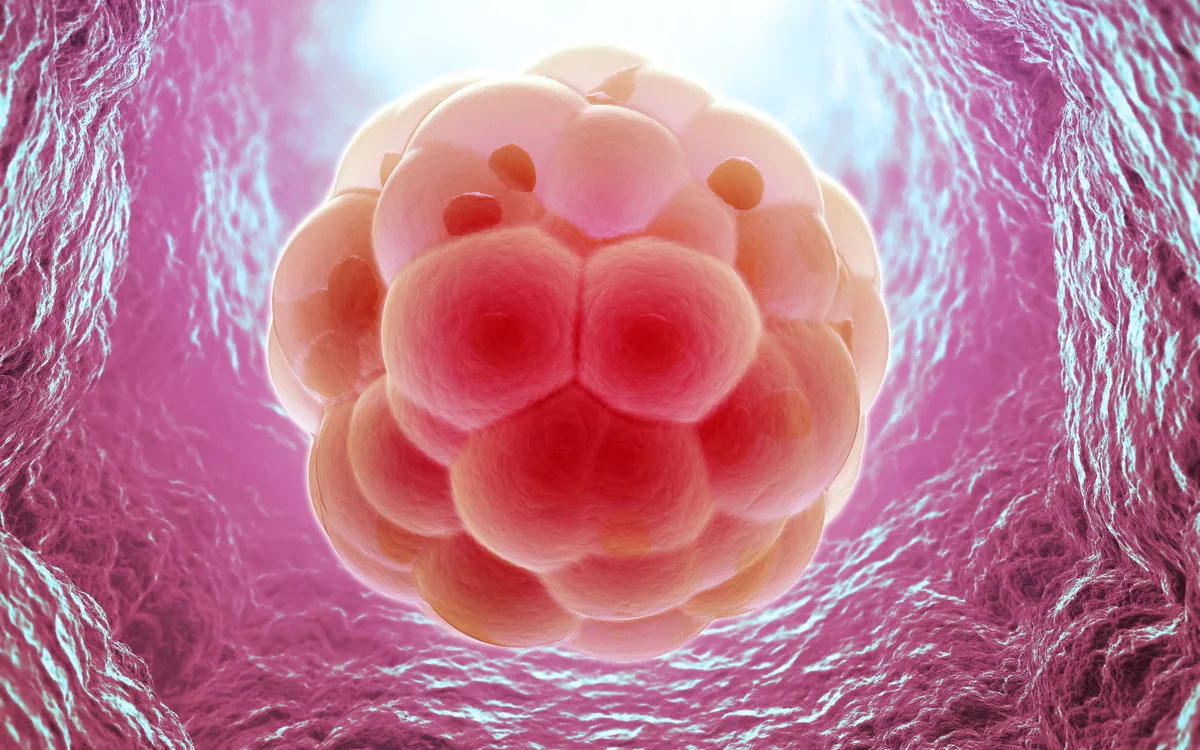

The reason I say this has to do with a just published study citing a failure to implant reprogrammed stem cells from an organism’s own body, thereby protecting them from becoming a target for the subject’s immune system as they try to repair the targeted tissues and organs. It turns out that activating the signals that encourage stem cells to develop new structures sets off the immune response and the seemingly friendly cells are now seen as pathogenic.

Whoops. The problem, it seems, lies with two genes, Zg16 and Hormad1. During a period in which a fetus is developing the distinction between its own tissues and that of foreign entities, these genes may be turned off while in the reprogrammed stem cells they’re active. As the stem cells try to grow into new shapes, the body’s defenses see these cells as intruders because they’re trying to differentiate and form structures when internal chemistry has turned off this kind of radical development. Forget about being able to internally grow new arms and legs; the cell cultures trying to diversify into them will be annihilated by your immune system.

While there’s data to suggest that your stem cells could conceivably be used to grow a new, mature heart or a lung or a liver and implanted back in with minimal fears of a rejection, using your own body’s processes to help out wouldn’t work and the technology needed to make it would have to be that much more complex than it is now. Now, it’s not that this finding completely eliminates the foundation for the key ideas behind regenerative medicine. This setback just tells scientists that there’s much more we need to know to make the process work and warns of the potential for more complications and problems down the road. Biology is just finicky like that.

This is partially why my last take on life extension and radical medicine focused on machinery rather than a biological answer. Every individual is somewhat unique and after billions of years of evolution, we have living things so bizarrely and intricately messy that changing something within them is fiendishly complex. Machine parts are mass produced and can be customized to work around and with biological limitations. We can use them to help build new organs and provide scaffolding and structure for developing stem cells, and one day, maybe even build new organs from bio-compatible materials that won’t be actively attacked by T cells, or with several mutations down the line develop tumors. So when something breaks and wears down, we can throw in new organs and joints to whatever extent biology will let us.

But our cells are certainly not just plug-and-play as some popular science journals and overly eager scientists hoped, and we need to make sure that we are as thorough as possible with new clinical ideas and don’t take our conclusions as automatically correct, even if they simply build on the fundamentals of existing theories. And this experiment is just a reminder that we do not know nearly as much as we sometimes tend to think and have a very long time before we can really wield our knowledge of biology’s building blocks to do truly amazing things with our bodies from the bottom up.

Zhao, T., et al. (2011). Immunogenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells Nature DOI: 10.1038/nature10135