why this year became the year of the protest

Apparently, 2011 has been the Year of the Protest, which is why Time Magazine saluted protesters around the world by naming a homogenized personification of them as its Person of the Year. And they’re right. There’s been a great deal of protesting across the world. In fact, Foreign Policy has a rundown on the protests in 50 nations, from the counties of the Arab Spring, to the United States. (One picture may be a bit NSFW since it’s one of the protests by the Ukrainian feminist group FEMEN, whose slogan is “I came, I got undressed, I won,” so you probably get the idea here.) But as people are taking to street in greater and greater numbers, we just have to wonder why. Certainly the use of social media to organize vast groups of like-minded activists had to have been a major contributor, but there had to have been something more than that driving the protesters. It may be easy to get a lot of sympathetic Twitter followers and Facebook friends, but the phenomenon of digital slacktivism tends to keep many of them firmly behind their computers. What motivates so many of them to go out and demand change? Maybe it’s as simple as having the right mix of economic malaise and frustration.

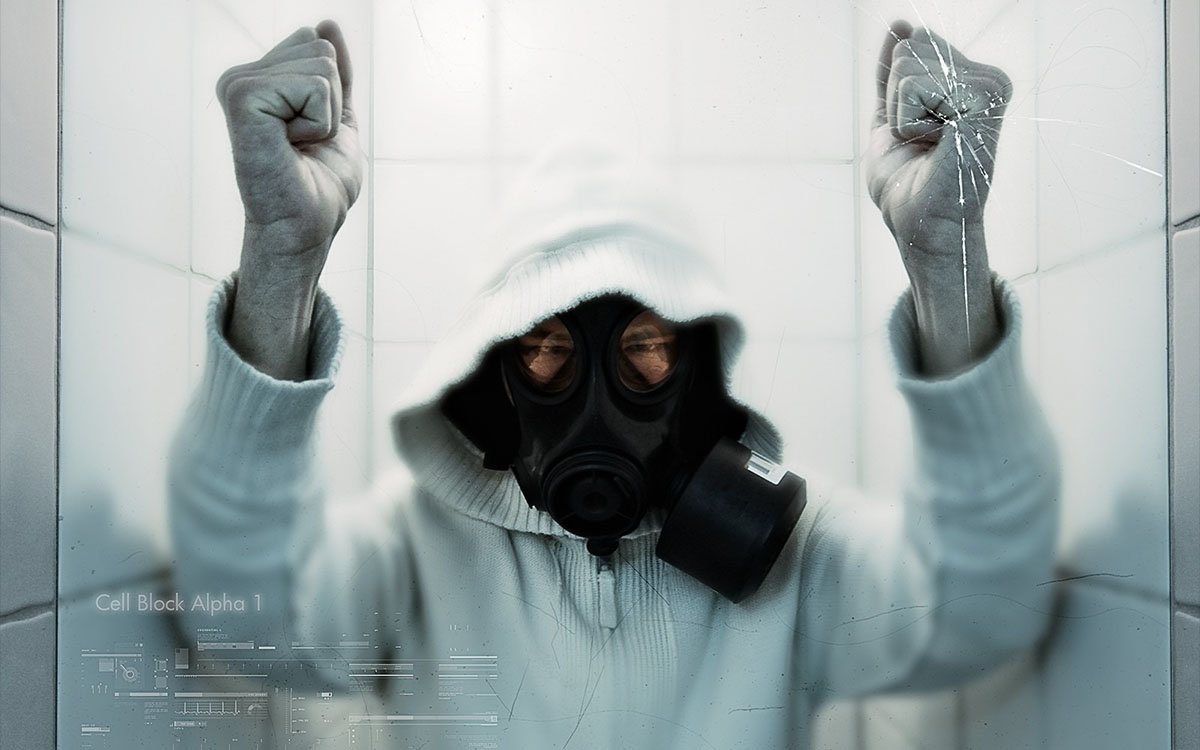

Of course, according to the autocrats against whom many of these protests were directed, the protests are a nefarious conspiracy concocted by an evil foreign government, by which they usually mean the United States, to destabilize their near perfect regimes and undermine their political standing in the world. But unless you’re extremely paranoid or are just very, very nationalistically zealous, it’s very unlikely that you’re buying this line of reasoning. After all, the nations to which the autocrats’ fingers point have their own protest movements. Good cover, right? Actually more like worldwide misery taking the form of angry demonstrators who want change of some sort, feeling frustrated and trapped in the status quo, ignored by those to whom their lives don’t matter, and those who profit off their positions of power with no consideration for how to help those in a rut. According to the old saying, a rising tide lifts all boats, but economically, we don’t really have a real rising tide and for the last five or six years, wages have been more or less stagnant while prices for everything continue to go up. In Europe and the Middle East, the members of Generation Y faced the most dire job prospects, able to get a few jobs to make a little spare change, but nothing in terms of a career that lets them make ends meet, which is why they’ve been credited with creating the biggest and most persistent protest movements of the year.

Sure, it’s easy for those older to scoff about how youngsters today are just a bunch of spoiled brats who think that everything should be handed to them and who won’t sully their hands with menial work. They will. It’s not as if there are no young menial workers out there. It’s just that they were constantly assured by their parents, their teachers, their guidance councilors, their college advisors, and even their politicians that their education would allow them to quit sorting paperwork or putting up drywall, and let them net them the job they wanted to start their own independent lives. Surprise surprise, it won’t. As a result, they are highly educated, but in debt and with very few prospects to get a job that will allow them to be independent. When they complain, they get derided by pundits in thousand dollar suits being paid millions a year to pontificate on topics with which they have only a cursory familiarity at best, and their concerns are dismissed as irrelevant. And so they go out and protest to be heard, to be taken seriously, and to have someone address the injustices they see happening around them, injustices such as layoffs to boost executive bonuses, lawmakers playing political football with issues which affect their livelihoods, and corruption which allows banks to crash economies with nary a slap on the wrist and concerned, but ultimately impotent tut-tutting from their campaign donation recipients.

Usually, even all that frustration could be bottled up since any authoritarian or political cynic knows that people will put up with a lot if they’re given the means to comfortably sustain themselves. The oligarchs of China even made an implicit bargain with their subjects; if the citizens don’t become politically involved, they’ll have a shot at being able to sustain themselves through new economic opportunities. The bargain works so well, that it’s actually a counterpoint to the idea that freedom of information promotes democracy, since so few Chinese will risk their jobs for something as intangible as political freedom. The protests taking root in China now are primarily about local issues and corrupt party bosses instead of calls for sweeping reforms and demands for the ruling party to step down and hold genuine elections. Those declarations may well land you under house arrest or in some far off torture chamber where you’ll be very sternly invited to rethink your stances on Chinese politics. In the West, where we have far more freedoms, we put up with corruption, yawning inequality, and an array of issues stemming from our officials’ political ineptitudes when times are good. When that paycheck is on our desk every other Friday, we take these problems to be inevitable but manageable. But when there’s no paycheck and no one seems to care about why it’s gone or how to fix it, they become very hard to ignore.

Why is it that when banks mess up they get loans on terrific terms but when the economic contagion created by those banks results in millions of jobs lost and widespread hiring freezes, those who ended up without a job are labeled lazy mooches and a massive political party wants to take every opportunity to deny them basic assistance while they try to find new jobs in a horrible economy with little success? Why is it what when given the task of actually leading, our leaders are stuck in a perpetual, immobile, borderline childish gridlock and play partisan games which cast viable questions and ideas as too taboo to even discuss? Didn’t we elect a good deal of them based on the idea that they could actually do what’s best for the nation rather than what will play best for the next election year’s campaign ads? Why do they let lobbyists write laws and lavish campaign donors with subsidies and pork barrels? After more than three years of such questions, it’s little wonder that this year was the year when those fed up with the status quo and the hoarding of money and power by venal, corrupt, and petty politicians and their friends organized into sit-ins, marches, and riots, demanding a change and a plan that actually takes then into the future and addresses real issues with real plans instead of vague, grandiose-sounded legislative band-aids diluted past the point of absurdity.