kurzweil’s new theory of mind: better, still wrong

Ray Kurzweil, the tech prophet reporters love to quote when it comes to our coming immortality courtesy of incredible machines being invented as we speak, despite his rather sketchy track record of predicting long term tech trends, has a new book laying out the blueprint for reverse-engineering the human mind. You see, in Kurzwelian theories, being able to map out the human brain means that we’ll be able to create a digital version of it, doing away with the neurons and replacing them with their digital equivalents while preserving your unique sense of self. His new ideas are definitely a step in the right direction and are much improved from his original notions of mind uploading, the ones that triggered many a back and forth with the Singularity Institute’s fellows and fans on this blog. Unfortunately, as reviewers astutely note, his conception of how a brain works on a macro scale is still simplistic to a glaring fault, so instead of a theory of how an artificial mind based off our brains should work, he presents vague, hopeful overviews.

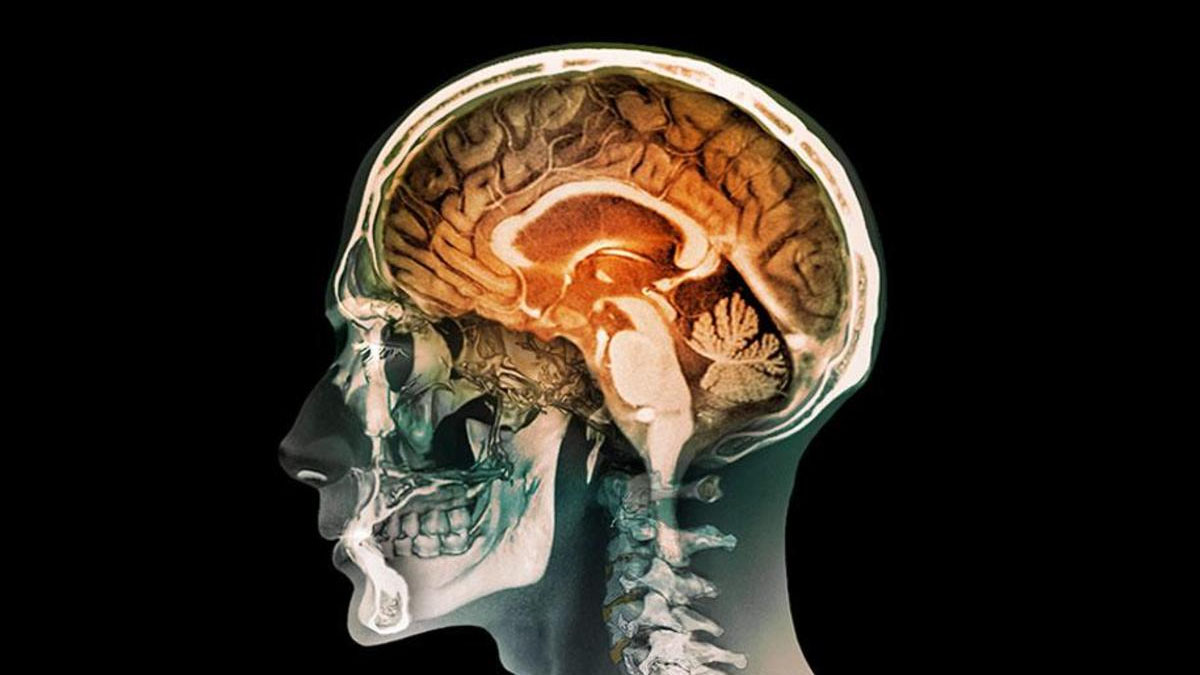

Here’s the problem. Using fMRI we can identify what parts of the brain seem to be involved in a particular process. If we see a certain cortex light up every time we’re testing a very specific skill in every test subject, it’s probably a safe bet that this cortex has something to do with the skill in question. However, we can’t really say with 100% certainty that this cortex is responsible for this skill because this cortex doesn’t work in a vacuum. There are hundreds of billions of neurons in the brain and at any given time, 99% of them are doing something. It would seem bizarre to get the sort of skin-deep look that fMRI can offer and draw sweeping conclusions without taking the constantly buzzing brain cells around an active area into account. How involved are they? How deep does a particular thought process go? What other nodes are involved? How much of that activity is noise and how much is signal? We’re just not sure. Neurons are so numerous and so active that tracing the entire connectome is a daunting task, especially when we consider that every connectome is unique, albeit with very general similarities across species.

We know enough to point to areas we think play key roles but we also know that areas can and do overlap, which means that we don’t necessarily have the full picture of how the brain carries out complex processes. But that doesn’t give Kurzweil pause as he boldly tries to explain how a computer would handle some sort of classification or behavioral task and arguing that since the brain can be separated into sections, it should also behave in much the same way. And since a brain and a computer could tackle the problem in a similar manner, he continues, we could swap out a certain part of the brain and replace it with a computer analog. This is how you would tend go about doing something so complex in a sci-fi movie based on speculative articles about the inner workings of the brain, but certainly not how you’d actually do that in the real world where brains are messy structures that evolved to be good at cognition, not to be compartmentalized machines with discrete problem-solving functions for each module. Just because they’ve been presented as such on a regular basis over the last few years, doesn’t mean they are.

Reverse-engineering the brain would be an amazing feat and there’s certainly a lot of excellent neuroscience being done. But if anything, this new research shows how complex the mind really is and how erroneous it is to simply assume that an fMRI blotch tells us the whole story. Those who actually do the research and study cognition certainly understand the caveats in the basic maps of brain function used today, but lot of popular, high profile neuroscience writers simply go for broke with bold, categorical statements about which part of the brain does what and how we could manipulate or even improve it citing just a few still speculative studies in support. Kurzweil is no different. Backed with papers which describe something he can use in support for his view of the human brain of being just an imperfect analog computer defined by the genome, he gives his readers the impression that we know a lot more than we really do and can take steps beyond those we can realistically take. But then again, keep in mind that Kurzweil’s goal is to make it to the year 2045, when he believes computers will make humans immortal, and at 64, he’s certainly very acutely aware of his own mortality, and needs to stay optimistic about his future…