why kepler-1625b, what a big moon you have…

When a pair of astronomers trying to validate data from the Kepler telescope got 40 hours worth of time with Hubble, they saw something spectacular as a planet known as Kepler-1625b crossed in front of its star. Just three and a half hours later, there was another dip in the star’s light, consistent with the transit of a moon following the planet “like a dog following its owner on a leash,” according to one of the researchers. Of course, this is exciting news in and of itself because it would be mind-boggling if we couldn’t find any moons in alien solar systems. Our own has more than 200 of them and they’re an integral part of how we think solar systems form.

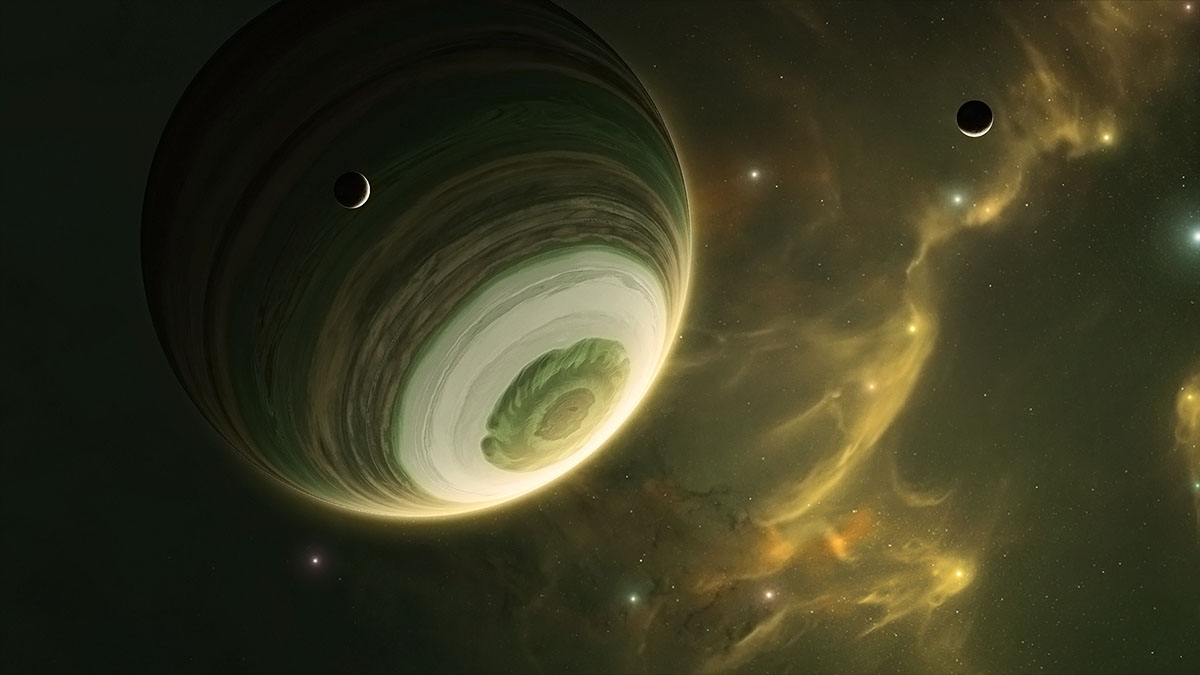

But the real surprise was the size of this exomoon. It’s roughly the size of Neptune, orbiting a planet with three times the mass of Jupiter. Incidentally, Kepler-1625b probably isn’t larger than Jupiter because once planets get to that size they generally just become more massive due to their own gravity, unless they’re close enough to get constantly bombarded by gusts of solar winds. In effect, we may be seeing a moon orbiting a planet more than a third of its size (and 1.5% of its mass) which raises the question of how it could have formed so close to such a powerful gravity well without being torn apart, or at least limited to the size of a large terrestrial planet.

Kepler-1625b would’ve drawn in a lot of comets, gas, and dust so it’s not completely out of the question that with enough luck, it helped spawn another gas giant in its orbit. And large moons aren’t exactly unknown in our solar system either. Our moon is just about a quarter the size of Earth with a sixth of our mass and Charon is more than half the size of Pluto, making some astronomers wonder if we should call Pluto a binary dwarf planet. (Although the topic of what to call Pluto in the first place is still a touchy subject.) So, perhaps there’s not really a limit on how big moons could get and it’s just a question of taxonomy.

Still, it’s rather difficult to imagine that a world trying to accrete enough gas and dust to graduate to giant status would do well bombarded by comets and asteroids attracted by its planet’s immense heft only 3 million kilometers away (or less than eight times farther than the distance between the Earth and the Moon, sneezing distance at those scales), then blasted by solar winds. Impact hypotheses also seem like a nonstarter because so much matter would have to be blasted off Kepler-1625b that we’re not sure how that collision would’ve taken place.

One possible solution to this dilemma could be viewing the moon as a captured planet. Hot Jupiters, or gas giants orbiting their stars in extreme proximity with orbital periods of a few days or less, are extremely common. They would have formed in the outer solar system where it’s cold and calm enough for them to grow to their full size, then collide with dust in protoplanetary disks and lose momentum. As their orbit decays, they might find themselves spiraling extremely close, if not straight into, their parent stars. During this process, they would disrupt the orbits of other planets along their way. Some may be ejected from the solar system, some fall into the star, and others might unwittingly become moons.

This may be what happened to Kepler-1625b’s satellite. As it fell towards the planet, it could have settled in the Hill Sphere, the space around the planet where its gravity dominates, and stabilized itself. A similar story is thought to have played out for Neptune’s moon Triton as evidenced by its retrograde, decaying orbit, or in other words, its backwards, unstable path around Neptune. We don’t know the full details of Kepler-1625b’s moon’s orbital path yet, but if it also has a retrograde orbit, that would be strong evidence that it’s an interplanetary refugee.

And here’s yet another interesting thing about this bizarre exomoon. Astronomer Phil Plait did a little math and hints that due to its size, it may be plausible for this moon to have moons of its own, like some sort of alien planetary matryoshka. Now, there are still observations to be done before all the data is confirmed, but so far, it’s looking very likely that nature once again surprised us with an object we never imagined could exist, just like it did with Hot Jupiters when we started looking for the first exoplanets.

See: Teachey, A., Kipping D., Evidence for a large exomoon orbiting Kepler-1625b. Science Advances, 2018; 4 (10) DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aav1784