did a solar storm set off underwater mines during the vietnam war?

Something very strange happened in August 4th of 1972 in the waters near Vietnam. Dozens of undersea mines detonated for seemingly no reason. The matter was classified, as was a report trying to get to the bottom of what happened. Initial hypotheses focused on a malfunctioning self-destruct feature meant to prevent lost mines from posing an underwater hazard for decades after hostilities were over, but there was no corroborating evidence. Soviet subs might have accounted for one or two, but not systematic detonations across the whole minefield, not to mention their defensive countermeasures.

But one of the suggestions seemed to very neatly explain the observed phenomenon. The mines were magnetic, meaning that they reacted to the natural magnetism of metals in ships’ hulls and the changes in the strengths of their magnetic fields as those ships approached. It was an old, reliable technology and it would’ve taken a massive magnetic event to have set them off. And wouldn’t you know it, some of the most intense solar activity on record happened in that exact time frame, causing numerous power surges and telegraph outages across North America.

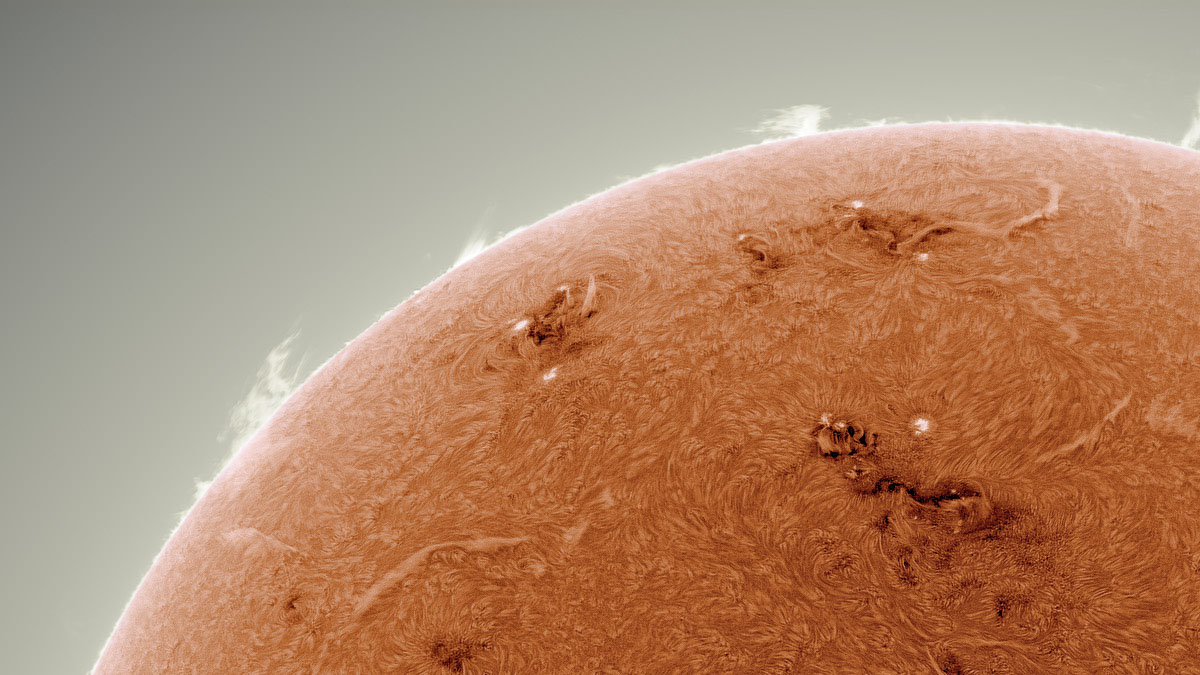

On the day Navy aircraft saw the mines go off, the sun erupted in what’s known as an X-class flare, a burst of energy more than 10,000 times more powerful than the high end of typical solar emissions. With the path to Earth cleared by supercharged solar winds, the resulting coronal mass ejection hit Earth in just 14.6 hours instead of the typical three days and caused massive magnetic and electrical disruptions in the atmosphere, quite possibly powerful enough to set off detectors on the underwater mines off the coast of Hon La Port as the plasma slammed into our planet.

So, case closed? Not exactly. We measure the intensity of the disruption in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by solar storms in negative nTs, or nano-Teslas. By itself, a nano-Tesla isn’t much. Your run of the mill fridge magnet is a million times stronger, although it’s only spread over tens of square centimeters, instead of millions of square kilometers like the fraction of a coronal mass ejection that hits Earth and lingers in the upper layers of the atmosphere. In 2003, a massive flare hit us with a magnetic disruption measuring almost -400 nT without melting anything down, although it did cause problems with air traffic.

By comparison, the ejection in 1972 measured a third of that at just -125 nT. Was it really strong enough to set off underwater mines? We’ll probably never know for sure, but it’s still entirely possible. Over the decades, we’ve learned much more about solar storms and what they can do, developed better shielding and early warning systems, more sophisticated equipment, and unwittingly created a shield of radio emissions to reroute charged particles from Earth. It’s quite plausible that older, less insulated technology was more sensitive to major solar storms and the trigger mechanisms for those mines were just one example.