why black holes have magnetic storms like stars

Using the tremendous resolving power of the ESO’s Very Large Telescope array in Chile, astronomers used the new GRAVITY instrument to detect the “wobble” of bright patches embedded inside the accretion disk that spins with the black hole. These bright features are clocking speeds of 30 percent the speed of light.

This is the first time any feature so close to a black hole’s event horizon has been seen and, using thirteen-year-old predictions by astrophysicists, we have a good idea about what’s causing the fireworks.

“It’s mind-boggling to actually witness material orbiting a massive black hole at 30 percent of the speed of light,” said scientist Oliver Pfuhl, of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics and co-investigator of the study published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. “GRAVITY’s tremendous sensitivity has allowed us to observe the accretion processes in real time in unprecedented detail.”

It is thought that the accretion disk surrounding a black hole is threaded with a powerful magnetic field that frequently becomes unstable and “reconnects.” Similar to the physics that drives the explosive flares in the Sun’s lower corona, these reconnection events rapidly accelerate the plasma in the disk, discharging vast quantities of radiation. These flaring events inside Sgr A*’s accretion disk create hotspots that get pulled in the direction of the material’s spin as it slowly gets digested by the black hole. The GRAVITY instrument was able to deduce that the accretion disk material is orbiting the black hole in a clockwise direction from our perspective and the accretion disk is almost face-on.

The original theory behind these hotspots was derived by Avery Broderick (University of Waterloo) and Avi Loeb (Harvard University) when they were both working at Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in the mid-2000s. In 2005 and 2006, the pair published papers that described theoretical computer models that simulated reconnection events in a black hole’s accretion disk, which caused intense heating and bright flares. The resulting hotspot would then continue to orbit with the speeding accretion disk material, cooling down and spreading out, before another instability and reconnection event would be triggered.

Their work was inspired by the detection of enigmatic bright flares erupting in the vicinity of Sgr A*. These flares were powerful and regular, occurring almost daily. At the time, a few theories were being explored—from supernovas detonating near the supermassive black hole, to asteroids straying too close to the black hole’s gravitational maw—but Broderick and Loeb decided to focus on the extreme region immediately surrounding the black hole’s event horizon.

“Avi and I thought: ‘well, if the flare timescales are close to orbital timescales around the black hole, wouldn’t it be interesting if they are actually bright features embedded in the accretion flow orbiting close to it?’,” Broderick told me.

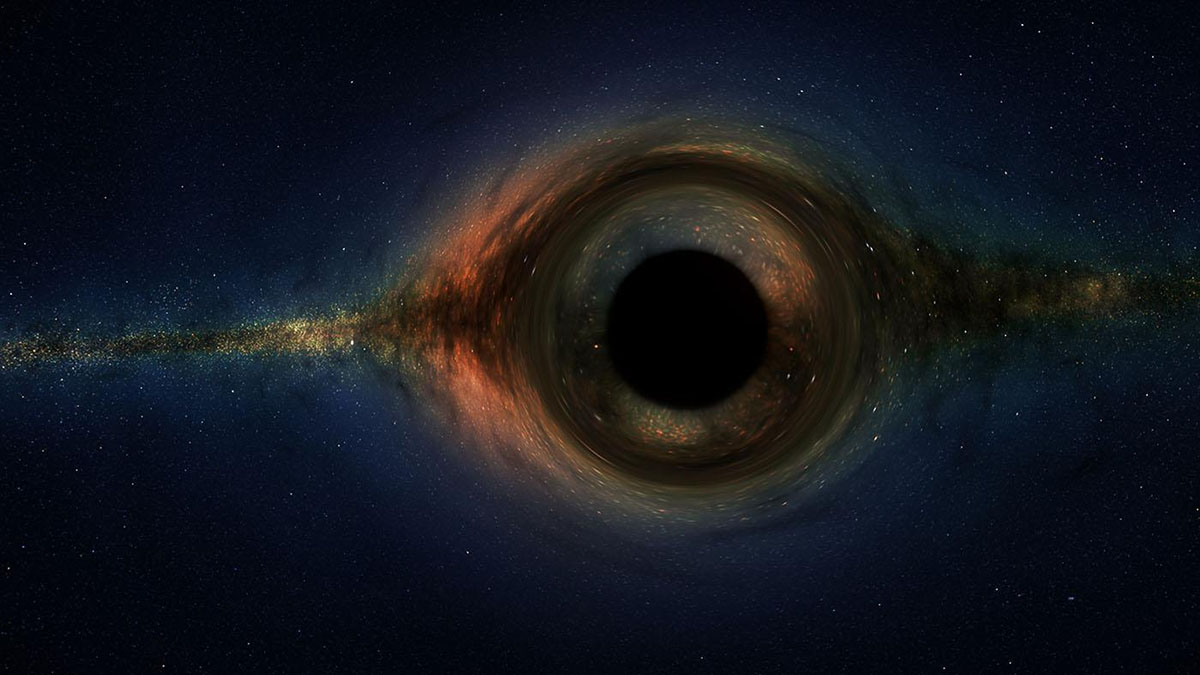

Black holes are gravitational masters of their domain; anything that drifts too close will be blended into a superheated disk of plasma surrounding them. The matter trapped in the accretion disk then flows toward the event horizon—the point at which nothing, not even light, can escape—and consumed by the black hole via mechanisms that aren’t yet fully understood. The researchers knew that if their model was an accurate depiction of what is going on in the core of our galaxy, these hotspots could be used as visual probes to trace out structures in the accretion disk and in space-time itself.

It’s Sgr A*’s gravity of 4 million Suns that gives the flares a super-boost, however. “In our orbiting hotspot model, a key component of the brightening is actually caused by gravitational lensing,” added Broderick, referring to a consequence of Einstein’s general relativity, when the gravity of black holes warp space-time so much as to form lenses that can magnify the light from distant astronomical sources. “It’s like a black hole analog of a lighthouse.”

Now that GRAVITY has confirmed the existence of these hotspots, Broderick is overjoyed.

“I’m still absorbing it; it’s extremely exciting,” he said. “I’m bouncing around a little bit! The fact you can track these flares is completely new, but we predicted that you could do this.”

The GRAVITY study is led by Roberto Abuter of the European Southern Observatory (ESO), in Garching, Germany, and it describes the detection of three flares emanating from Sgr A* earlier this year. Although the hotspots cannot be fully resolved by the VLT, with the help of Broderick and Loeb’s predictions, Abuter’s team recognized the “wobble” of emissions from the flares as their associated hotspots orbited the supermassive black hole.

This discovery opens a brand-new understanding of the environment immediately surrounding Sgr A* and will complement observations made by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), an international collaboration of radio telescopes that are currently taking data to acquire the first image of a black hole, which is expected early next year.

Broderick hopes that these advances will help us to understand how black holes grow and consume matter, and if the predictions of general relativity break down at one of the most gravitationally extreme environments in the universe. But he’s most excited about how the first EHT image of a black hole will impact society as a whole: “It’s going to be a wonderful event, I think it will be an iconic image and it will make black holes real to a lot of people, including a lot of scientists,” he said.

As an aside: In 2016, I had the incredible good fortune to visit the VLT at the ESO’s Paranal Observatory as part of the #MeetESO event. I interviewed several VLT and ALMA scientists, including Oliver Pfuhl, and helped produce the mini-documentary below…

[ this article originally appeared on astroengine ]