wonky star systems may be born that way

Textbook descriptions of our solar system often give the impression that all the planets orbit the sun in well-behaved near-circular orbits. Sure, there’s a few anomalies, but, in general, we’re led to believe that everything in our interplanetary neighborhood travels around the sun around a flat orbital plane. This, however, isn’t exactly accurate.

Pluto, for example, has an orbit around the sun that is tilted by over 17 degrees out of the plane of the ecliptic (an imaginary flat plane around which the Earth orbits the sun). Mercury has an inclination of seven degrees. Even Venus likes to misbehave and has an orbital inclination of over three degrees. If all the material that built the planets originated from the same protoplanetary disk that was — as all the artist’s impressions would have us believe — flat, what knocked all the planet’s out of alignment with the ecliptic?

Until now, it was assumed that, during the early epoch of our solar system’s planet-forming days, dynamic chaos ruled. Planets jostled for gravitational dominance, Jupiter bullied smaller worlds into other orbits (possibly chucking one or two unfortunates into deep space), and gravitational instabilities threw the rest into disorderly orbital paths. Other star systems also exhibit this orbital disorder, so perhaps it’s just an orbital consequence of a star system’s growing pains.

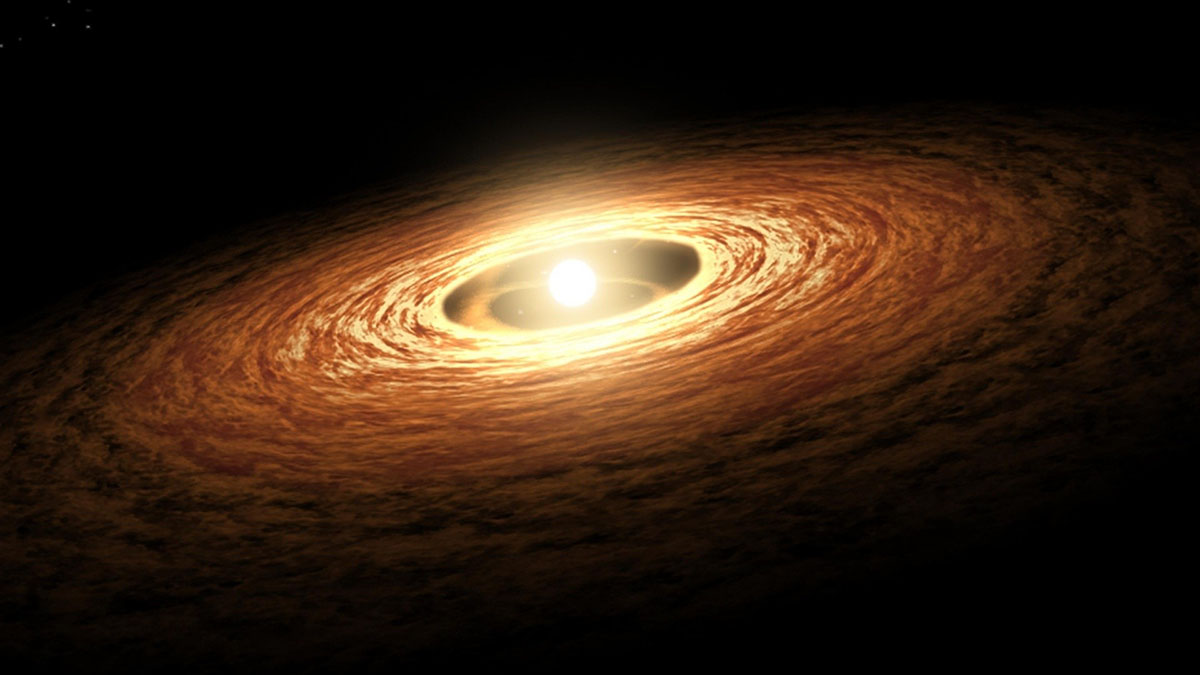

But there might be another contribution to the chaos: perhaps wonky star systems were just born that way. Cue a recent observation campaign of the nearby baby star L1527. Located 450 light-years away in the direction of the Taurus Molecular Cloud, L1527 is a protostar embedded in a thick protoplanetry disk. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), in Chile, astronomers of the RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research (CPR) and Chiba University in Japan discovered that the L1527 disk is actually two disks morphed into one — both of which are out of alignment with one another. Imagine a vinyl record that has been left on a heater and you wouldn’t be far off visualizing what this baby star system looks like.

The RIKEN study, published on Jan. 1 in Nature, suggests that this warping may have been caused by jets of material emanating from the star’s birth, kicking planet-forming material into this warped configuration and, should this configuration remain stable, could result in planets with orbital planes that are significantly out of alignment.

“This observation shows that it is conceivable that the misalignment of planetary orbits can be caused by a warp structure formed in the earliest stages of planetary formation,” said team leader Nami Sakai in a RIKEN press release. “We will have to investigate more systems to find out if this is a common phenomenon or not.”

It’s interesting to think that if this protoplanetary disk warping is due to the mechanics behind the formation of the star itself, we might be able to look at mature star systems to see the ancient fingerprint of a star’s earliest outbursts or, possibly, its initial magnetic environment.

It’s possible “that irregularities in the flow of gas and dust in the protostellar cloud are still preserved and manifest themselves as the warped disk,” added Sakai. “A second possibility is that the magnetic field of the protostar is in a different plane from the rotational plane of the disk, and that the inner disk is being pulled into a different plane from the rest of the disk by the magnetic field.”

Though orbital chaos undoubtedly contributed to how our solar system looks today, with help of this research, we may be also getting a glimpse of how warped our sun’s protoplanetry disk may have been before the planets even formed.

[ this article originally appeared on Astroengine ]