did we cure hiv? actually, we don’t know…

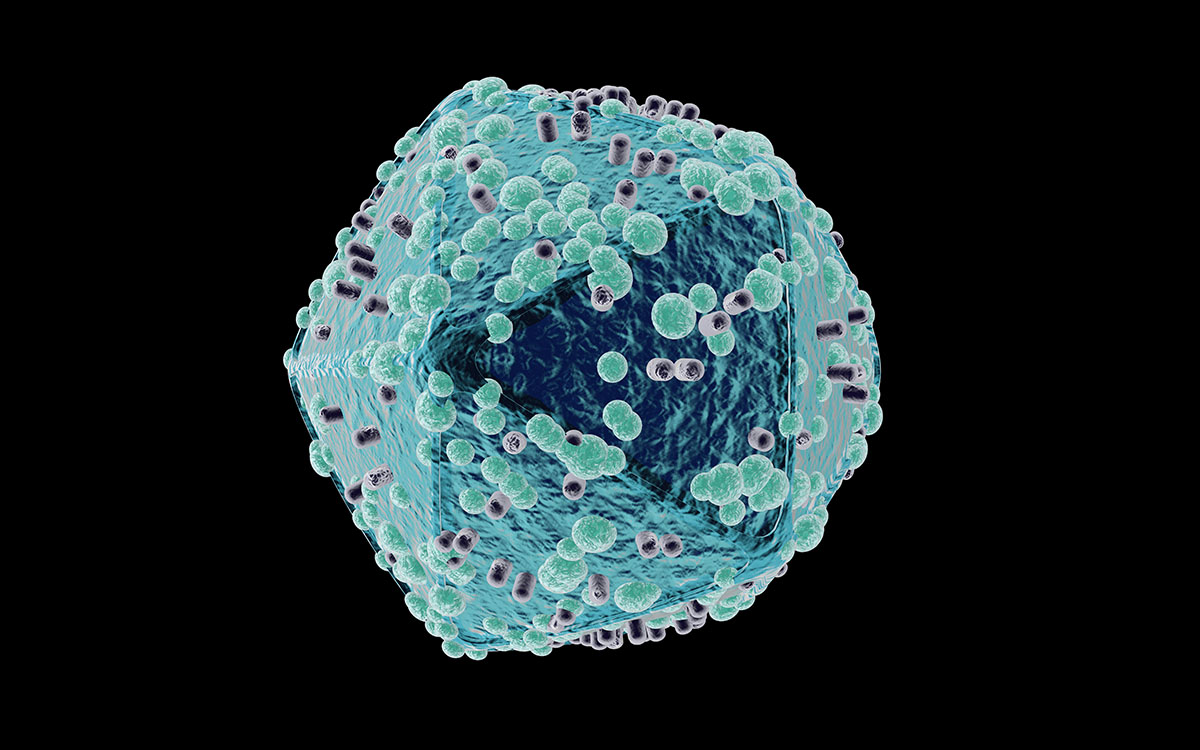

When the first cases of HIV appeared in the 1980s, a positive diagnosis was a death sentence. Instead of killing you, the virus attacks your immune system and leaves your body open to a variety of other maladies that will eventually take you down. A type of drugs called antiretrovirals can only keep the disease at bay while researchers try to find a vaccine or a cure which seemed so close, yet so far away for the last three decades. But there’s finally a glimmer of hope. After a bone marrow transplant from a donor with a mutation in the CCR5 protein, which makes cells resistant to HIV, a patient remained virus-free 18 months after his last dose of medication.

These results also seem promising thanks to the case of “the Berlin patient” Timothy Brown, who underwent a similar procedure and remained virus-free for 12 years. But there was a catch. Brown needed two bone marrow transplants and nearly died from graft-versus-host disease, or GVHD, afterwards. He was also given harsh chemotherapy and potent immunosuppressants to prevent his body from rejecting the transplanted cells with a regimen that was modified over the last decade to be less destructive. Doctors were trying to aggressively treat his leukemia, and eliminating the HIV was a complete fluke which researchers hoped to replicate.

Likewise, the man referred to as “the London patient” found himself being treated for cancer and his body rid of HIV as far as existing hypersensitive tests can tell. While this is promising, there’s worry and skepticism from doctors who aren’t sure how long a patient should be free of HIV to be considered cured. The London patient may be in remission and the virus could return. Plus, there’s a very sober concern that a bone marrow transplant in an attempt to cure the disease is not without its dangers. Brown almost died from complications, and it’s unlikely that the London patient found himself quickly leaping out of bed virus-free and healthy as his immune system was being rebuilt.

But that said, his treatment was much less intense and he did not suffer from the same nearly fatal complications as Brown as the transplanted cells killed both the cancer and HIV, and went on to replace his compromised immune system. So far, he’s the only other patient to receive this treatment and remain virus free for more than nine months, following what doctors described as a similar trajectory as Brown. At the same time, experts agree that if the CCR5 mutation is truly a potential cure for HIV, there has to be a safer, more effective way to introduce it than with a protocol intended to aggressively treat cancer.

This is why CCR5 gene edited stem cell infusions and gene therapy are being considered the way forward, although those experiments are very much in the proof of concept stage with very small patient groups. While there would be risks, these treatments wouldn’t be as severe and intensive as bone marrow transplants, and while there are doubts whether they’ll work reliably, there are still questions around the efficacy of the existing procedure with only one case which doctors are comfortable calling a cure, and one they’d prefer to treat as a remission while more research is done, citing cases in which patients went into remissions without any sort of bone marrow transplants or stem cell infusions.

Another concern is that there are multiple strains of HIV and current methods can only treat one of them, which is why another promising approach focuses on powerful antibodies to force the virus into remission. At best, Brown and the London patient are inspirational cases confirm that there is some potential in using the CCR5 mutation in the fight against HIV and after more than a decade of replication failures, we’re seeing evidence that we can defeat the virus for good. But as far as finding a reliable, workable cure for the tens of millions around the world who still suffer from this disease and have to take medication every day to stay alive? There are still years of work and many studies to be done.