why nasa may be trying to quietly put the sls out of its misery

NASA’s powerful heavy lift rocket appears to be in trouble yet again as the agency is openly considering hiring commercial spacecraft to ferry astronauts and heavy cargo into orbit, and letting the Space Launch System dangle with a vague request for more time. And while there’s nothing wrong or problematic with needing more time to make sure your rocket is built the right way and can do the job you designed it to do, there is a problem with hiring someone else to do the exact job for which that rocket is being developed. If NASA is insistent on taking a test lap around the Moon in a new crew vehicle in June of 2020, even if it means the SLS stays on the ground, and succeeds, why exactly will it need the SLS for the second lap?

Continuing that logic, if commercial rockets are doing fine and carrying everything that needs to be carried to the Moon cheaply and effectively enough, why would the SLS be needed at all? A landing without it seems like a real possibility, and if NASA is giving companies like SpaceX and ULA enough breathing room to prove they can do it, there will be no real rationale for the launch system aside from being a jobs program for certain districts. And that prompts the question if this is an attempt to mothball the SLS. Now, it’s not easy to kill a large government program we just noted is used to create jobs in certain districts. But it can be done with the SLS.

Unlike military contracts, spacecraft development is far from a top priority, and we could see a transition away from the SLS toward other projects, killing the program after buying enough time to do it gently. From a logistics and economic perspective, it would make perfect sense to end a project no one except Congress seemed to really want. The end result was going to be far too expensive and wasteful compared to SpaceX’s reusable rockets, costing taxpayers roughly $1 billion per launch instead of an estimated maximum of $150 million, carrying about twice the payload for seven times the price, and without the ability to reuse any of the rocket to achieve any semblance of cost control.

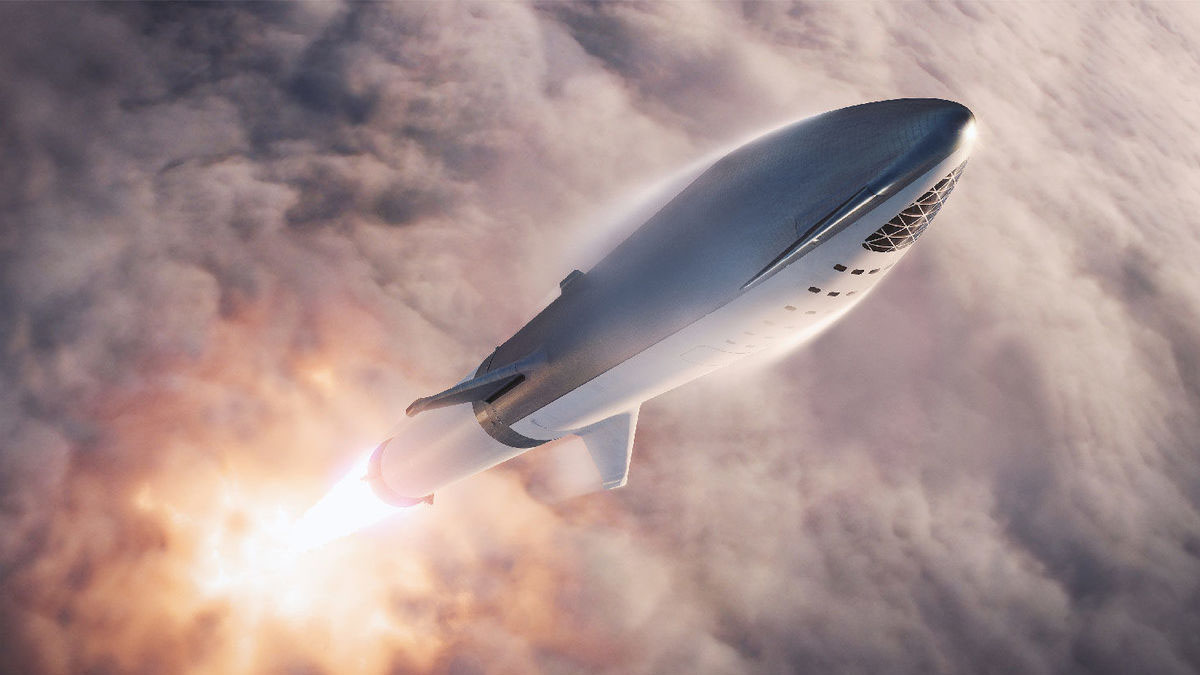

Yes, we might have to launch a mission in three phases, but we’d still get it where it needs to go and be 50% under our launch budget. And the disparity will be even more glaring as the BFR comes online and carries the planned maximum of the SLS for the same price as the Falcon Heavy, if not a little bit cheaper, since SpaceX plans to make the whole rocket fully reusable. In other words, the SLS hasn’t even been assembled and hoisted onto a launch pad, but it’s already basically obsolete and the longer its milestones keep slipping, the farther ahead commercial aerospace companies will pull. At the rate we’re going, it’s likely that the return to the lunar surface and the first steps on Mars will be done by spacecraft rented by space agencies instead of designed and built to their specifications.

But none of this is bad news. It gives space agencies around the world the capacity and extra budgets to do more science and exploration, to design more interesting experiments and learn more about our universe, and assign their employees to design completely new missions. It also allows nations who have to collaborate with others to send their astronauts into space to more or less buy their own rockets from SpaceX, ULA, or Ariane, set up launch pads, and send their crews and robots into orbit and beyond. As long as no international treaties are violated, there should be no problems buying a whole fleet of reusable launch vehicles and signing contracts to service and refurbish them after they’ve been flown.

This would be exactly the kind of revolution in space exploration so many optimists have been predicting, and it seems like it’s on our doorstep. Letting the SLS die with dignity wouldn’t be a setback for the American space program, especially in light of private companies’ impressive track record of getting things into space in the last few years. Just the opposite. It would be a big step for the future of space flight, freeing NASA to venture further than it ever has before, and helping its current partners expand their own programs and join in on larger and more ambitious missions that would’ve been too cost prohibitive or logistically difficult with old-fashioned, costly hardware mandated by more by political, rather than engineering, demands.