how google learned to stop trying to make cold fusion happen

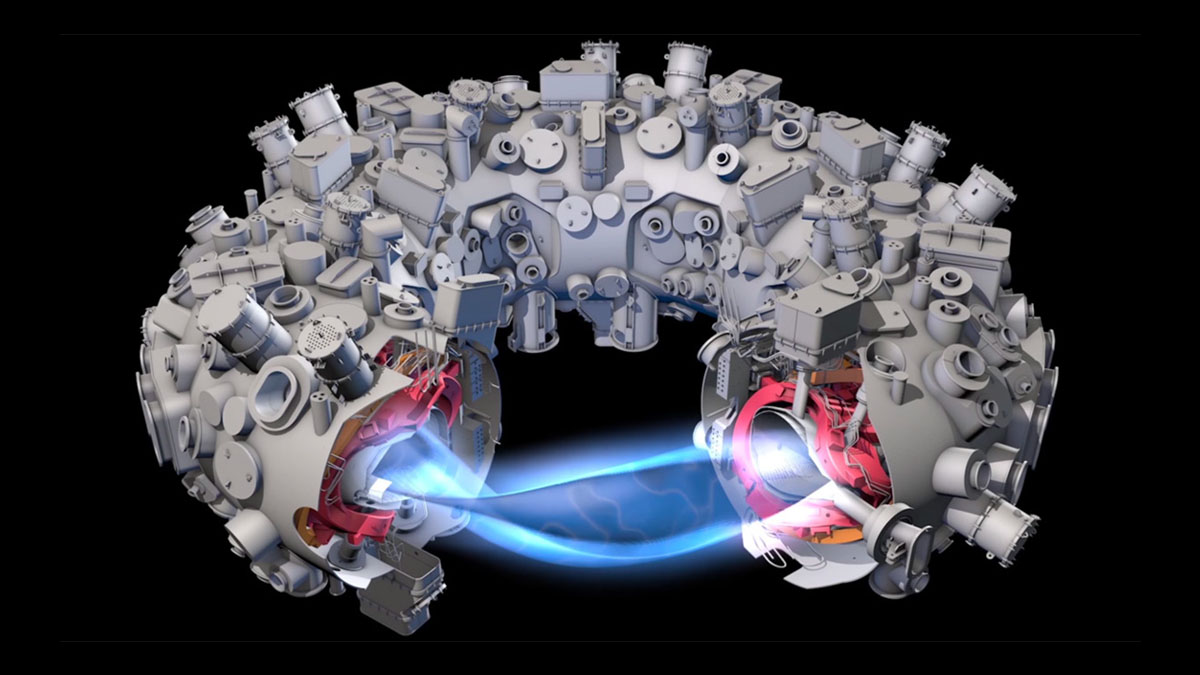

One of the most important rules in science it to leave no stone unturned, and Google seems to have taken that to heart when commissioning a study into whether a phenomenon known as cold fusion is really possible. To the surprise of pretty much no one, they came up empty because if there was some way to fuse atoms without temperatures exceeding 100 million degrees, or gravity generated by the equivalent of 32,000 times the mass of our planet, researchers who spent the last 60 years looking for shortcuts to make fusion a viable energy source would have found at least some evidence for it. It would be a lot easier than trying to wrangle the artificial storms of plasma with enormous electromagnets in precisely engineered reactors the size of small office buildings at great expense and fighting for every research dollar to conduct the next test.

Just don’t tell that to a devoted group of conspiracy theorists sure that cold fusion is not only possible, but already exists and is being hidden by corporate interests not ready to move on from fossil fuels and nuclear fission, or alternatively, being suppressed by a hot fusion cabal terrified of losing their jobs as if physicists and engineers will suddenly be irrelevant to building cold fusion reactors. They believe this so strongly, they were more than happy to defend even obvious scams by those claiming to have cracked it, then hid their supposedly ready for wide commercial use reactors from public view. As far as they’re concerned, the proof is in papers which claim to detect tiny anomalies in tabletop experiments no one has replicated despite numerous attempts by multiple experts and institutions.

But that’s how it works in the conspiracy world. Solutions to complicated problems aren’t just simple, they’re already been implemented and could be used as soon as a convenient villain is toppled. In reality, however, any interaction between atoms and particles is governed by one of the fundamental forces of nature: electromagnetism. All matter has a negative charge and particles repel each through what’s known as the Coulomb barrier. While you can circumvent it with antimatter, which has a positive charge, allowing matter and antimatter to attract each other and unwinding their constituent particles in the process, matter-antimatter annihilation isn’t practical for either energy generation or weapons without a huge breakthrough.

The second way to overcome the barrier in question is to put energy into the system until the atoms get close enough to each other for the strong nuclear force to become more important than electromagnetism and atoms could combine electrons, neutrons, and protons. And this is the problem with cold fusion. It posits that at least some scenarios, electromagnetism that’s keeping atoms from getting too close to each other to fuse is like a distracted cop, and while it’s looking away, atoms can combine in low energy events. Is it possible? Maybe. But it would be a weird oversight in the Standard Model, which proved to be so successful that particle physicists were worried about where the discipline would go after confirming the existence of the Higgs particle until they detected weird particles in an Antarctic observatory.

And that brings up to the three biggest problems with cold fusion. The first is that if it’s indeed happening, and manifesting itself with very low energies involved, it’s probably not going to be viable as a power source because it’s not putting out a whole lot of power for us to capture. The second is that the evidence presented for it is well within the margins of error in experiments that are hardly airtight, so it’s a almost given that it vanishes in a stricter and better controlled replication effort. And the third, and final, is that none of it agrees with the Standard Model in a field where being able to either fit into the model or add on to it is a prerequisite after decades of unsuccessful attempts to prove it wrong in the world’s most powerful colliders by just about every expert in the discipline. Until all three of these somehow manage to change, every effort to investigate cold fusion is doomed to failure.