the dirty work of training an artificial intelligence

In the HBO series Silicon Valley, wannabe venture capitalist Erlich Bachman and his charge Jian-Yang are trying to make an artificial intelligence app that identifies pictures of food but found itself limited to identifying whether it was looking at a hot dog or not. In order to train it to see more than the binary choice between hot dogs and everything else, Bachman finagles his way into teaching a computer science class and asks the students to standardize, upload, and pre-process thousands of pictures of food to train the neural network in the app. The students are not having it, of course, because they’re there to learn how to build an AI, not to work as unpaid interns for a desperate has-been trying to cash in on a “Shazam for food” he pitched to an equally desperate venture capitalist.

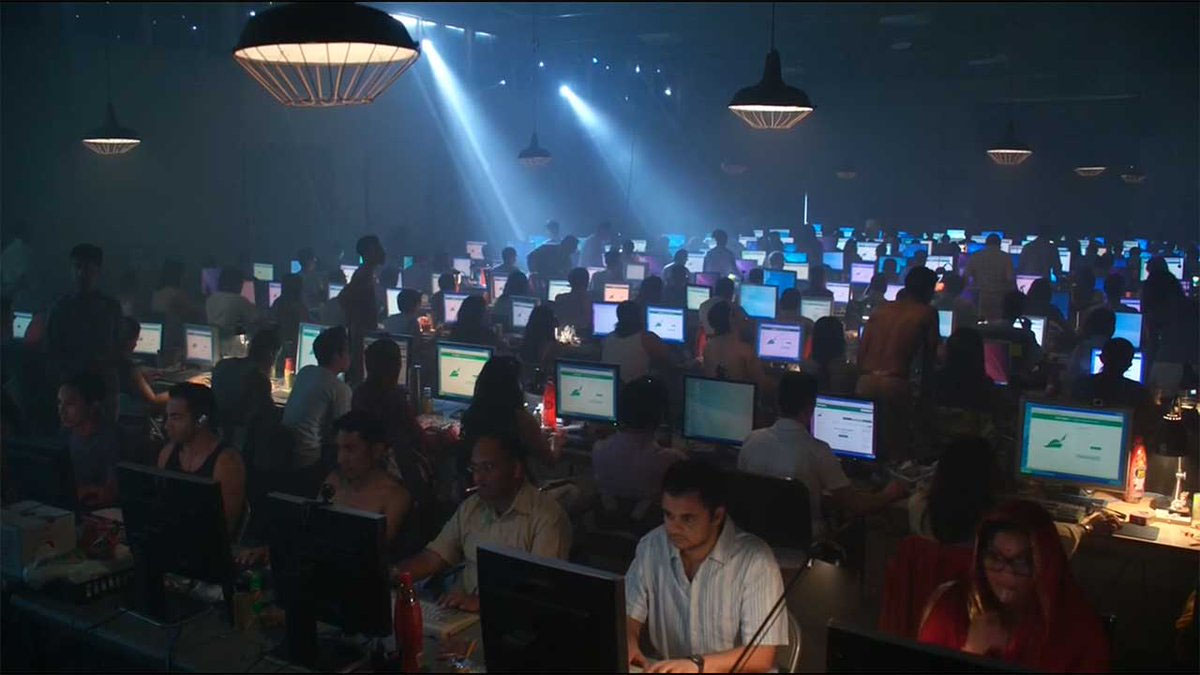

While this background story was played for laughs and satire, those who understand how the AI industry works saw it as an acknowledgment of tech’s seedy underbelly. Without a network of hundreds of thousands of contractors working around the world, today’s advances in artificial intelligence would’ve come a lot slower, and a lot of rough edges and mistakes would’ve been far more visible. Stanford students scoffing at doing menial work to standardize and label the training set for a new app may be a punchline, but that work needs to be done by someone if the network has any chance of understanding at what it’s looking, and it’s usually done by an army of underpaid laborers who act as ghostwriters for a piece of code that gets all the credit for their hard work. And this reliance on so-called “ghost work” is worrying experts.

say hello to big tech’s “ghost workers”

It’s not just the working conditions that have them concerned, it’s the concerted effort of the companies that employ them to pretend they don’t exist unless they really have to and paying them to automate their own jobs in the long run. Imagine having to come to work where you assemble different types of furniture step by step as a robot watches and tries to replicate your work while you correct its missteps, knowing that once it can work on its own roughly 90% of the time, you’ll be laid off and have to find new robots to train. Meanwhile, your company’s executives talk about how amazing the robots you are at making furniture, and when asked about the work you do, downplay it as much as they can as not to admit that their machines are anything but technical marvels.

And this is going to be a huge problem for you because when you’re out of sight, you’re also out of mind. No one needs to care about people who don’t officially exist, or if they do, are only a temporary presence on an as-needed basis, not the customers, not the official full-time workers of the companies in question, and certainly not the executives who outsourced a solution to a problem and have no intention in being involved in the day to day management of the workers training the machines until the machines can take over. Where do they go when their jobs are over? Irrelevant. The company building the AI never officially hired them, they hired another company which in turn employs them as contractors only for as long as they’re needed for both cost control and PR purposes. In other words, they’re nobody’s problem.

sixty ways to hide your workforce

Again, it’s important to note that there aren’t villains sitting in West Coast offices with scenic views of oceans and mountains either performing the finger pyramid of evil contemplation or twirling their moustaches, as some anti-tech industry pundits have proclaimed. They’ve sold their vision of powerful code automating thankless, tedious, or time-consuming tasks. If they were to finish every presentation of their new features with “and thanks to a team of 17,000 contractors for processing all the millions of data points we needed to even start debugging our product,” a lot of investors will get worried about the speed at which company will have to burn through cash to bring more features to market and support its products.

Unfortunately, by sweeping the challenges of building and training useful AI in the process, they’ve effectively developed a gig economy for an educated workforce with an aptitude for high tech fields but with no few options for turning their six month to a year gigs into steady careers. While it’s certainly possible, it requires employers looking for transferable skills and willing to provide training and mentoring options, and those employers are disturbingly rare nowadays. And that over-reliance on contractors alongside their systematic othering of those contractors what has the experts watching “ghost workers” really concerned.

how we’ve come full circle

A few odd jobs here and there training an artificial intelligence or two and you’re on the fast track to nowhere in particular, and nobody cares what happens to you because they barely even know you exist and would rather not care. And that’s ultimately what the problem boils down to. No one seems to care what happens in the long term, only what works for the next quarter then wonders why there are so many aimless, underpaid, overworked, and angry people rattling establishments all over the West or channeling their anger into conspiracy theories and populism. The politicians, CEOs, bankers, and VCs will sagely nod, and sigh “if only somebody did something.” Not them, of course. But somebody really should figure out where we go from here.

And it’s important to note that we’ve been here before. The gig economy is nothing new. It’s the 130 years of factory-driven regular, 9-to-5-30-years-then-retire employment that’s the aberration in humanity’s history. Industrialization was essentially a transitional period sold to us as a source of perpetual jobs and prosperity, but now that it’s coming to an end and machines are taking over, we have very little choice but to the rethink both the 9 to 5 arrangement and the pointless workaholism for the sake of workaholism trying to replace it with temporary busywork that will also likely end up being done by code and machinery. We have to set our sights higher and think bigger, and at some point we will because we’ll have no choice. But the sooner we start, the sooner we can end up with a long term plan for the post-industrial order, saving millions of jobs and maybe even lives.