it’s no teegarden party: the catch about the latest exoplanetary discovery

The universe is stranger than we can imagine, so when a star system is discovered with some familiar traits to ours, it can be hard not to imagine extraterrestrial lifeforms and interstellar getaways. But before you dream of bathing on the exotic shores of Teegarden b, breathing in the moist and salty air, while sipping on a Teegarden Tequila Sunrise, keep in mind that the reality will likely be, well, much stranger than we can imagine. So, what is all the fuss about Teegarden’s Star?

Last week, astronomers announced the discovery of two “habitable zone” exoplanets orbiting the tiny red dwarf star, which is located a mere interstellar stone’s throw away. While 12.5 light-years may sound like quite the trek, in galactic distances, that’s no distance at all. The two exoplanets, Teegarden b and c, are now in a very exclusive club, being the joint fourth-nearest habitable zone exoplanets to Earth (after Proxima Centauri b, Tau Ceti b and GJ 273 b). On the Earth Similarity Index (ESI), however, we have a new champion: Teegarden b — after considering its mass and derived surface temperature — this fascinating world is 95% “Earth-similar,” according to Abel Mendez’s analysis at the Planetary Habitability Laboratory (PHL). And like TRAPPIST-1, there’s some optimism that there should be more small exoplanets, some that may also be habitable, that have yet to be discovered around Teegarden.

All of these facts are cause for celebration, no? They are, but a heavy dose of reality needs to be applied when it comes to any world that has been discovered beyond our solar system.

more exoplanets, more possibilities

As alien planet-hunting missions continue to add more worlds to the vast menagerie of known exoplanets that exist in our galaxy, an increasing number of them are falling inside the “habitable zone” category.

The habitable zone around any star is the distance at which a rocky planet can orbit where it’s neither too hot or too cold for liquid water to exist on its surface (if it has water, that is). Liquid water is the stuff that Earth-like biology has an affinity to; without it, life on Earth wouldn’t have evolved. So, even before we have any clue about its H2O-ness, if an exoplanet is seen to have an orbit around its star that is deemed habitable, that’s +1 point for habitability.

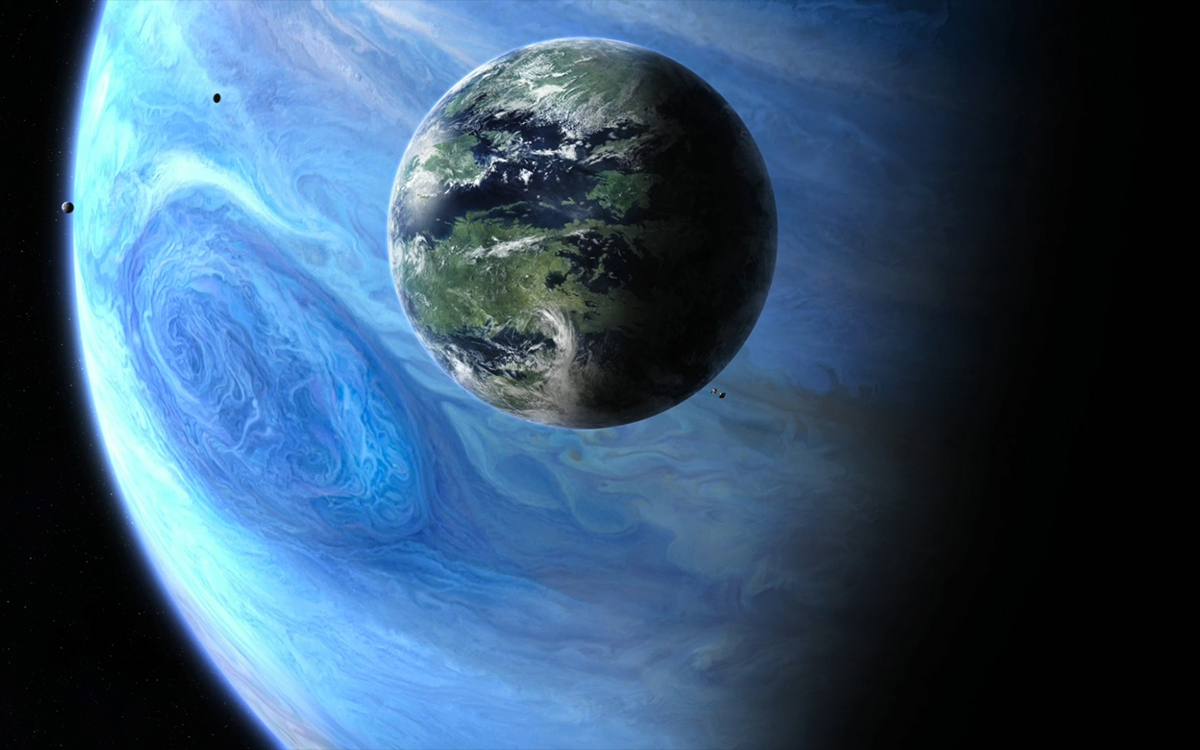

Now, the next point can only be won if that world is also of approximate Earth-like size and/or mass. There would be little reason in getting too excited for a Jupiter-sized exoplanet sitting in the habitable zone possessing liquid water on its “surface” (because it won’t have a surface). That’s not to say there can’t be some gas giant-dwelling balloon-like alien living in there, but we’re looking for Earth-like qualities, not awesome alien qualities we read in science fiction. (I’d also argue that these kinds of exoplanets might have habitable Earth-sized moons — like Avatar‘s Pandora — but that’s for another article…)

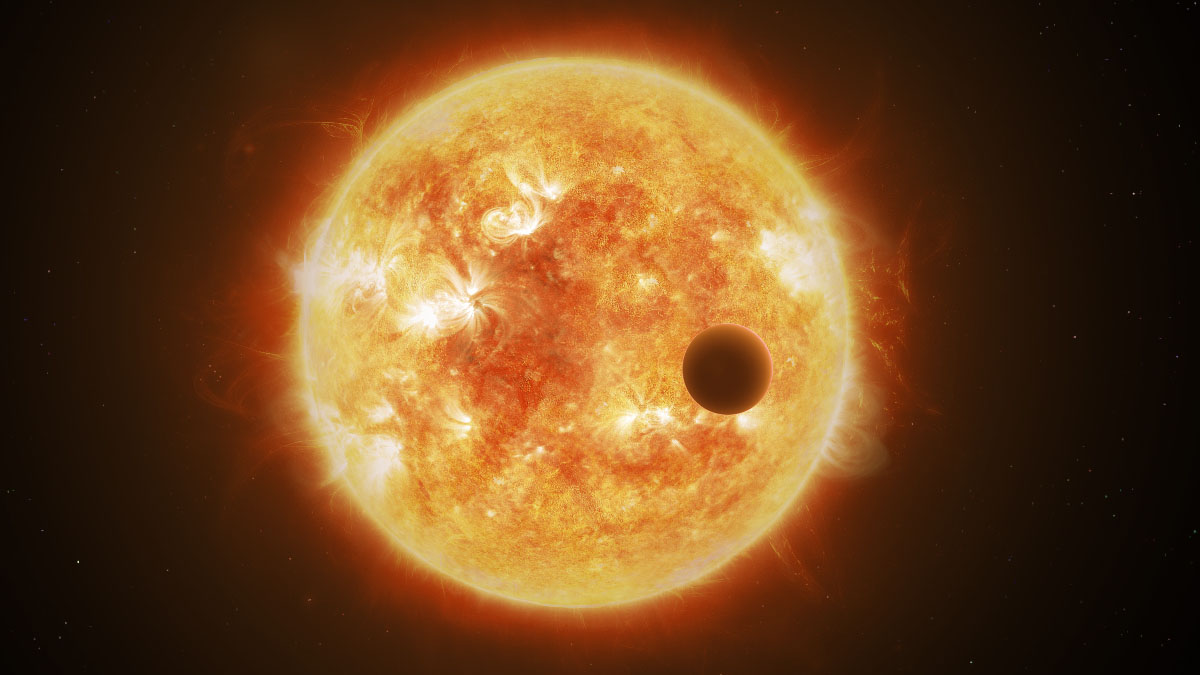

The two key methods for exoplanet detection is the “radial velocity” method and the “transit” method. The former — which precisely measures a star’s light to detect tiny stellar wobbles as an exoplanet gravitationally “tugs” at it as it orbits — can deduce the exoplanet’s mass, thereby revealing whether or not it has an Earth-like mass (Teegarden’s two worlds were discovered using this method). The latter — which was employed by NASA’s Kepler space telescope (and now NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Explorer, among others) to look for the slight dips in brightness as an exoplanet passes in front of its star — can deduce the exoplanet’s physical size, thereby revealing whether or not it has an Earth-like size. Should a habitable zone exoplanet possess either one of these Earth-like qualities, or both (if both methods are used on a target star), that’s another +1 point for its habitability.

There’s a few other measurements that astronomers can make that may add to a hypothetical world’s habitability (such as observations of the host star’s flaring activity, age, or some other derived measurement), but until we develop more powerful observatories on Earth and in space, there are several factors that quickly cause our hypothetical exoplanet to diminish in habitable potential.

the unhabitability of “habitable” worlds

So far in our burgeoning age of exoplanetary studies, we’ve only been able to measure (and derive) a handful of characteristics — such as mass, orbital period, physical size, density — but we have very little idea about these habitable zone exoplanets’ atmospheres. Apart from measurements of a few massive and extreme exoplanets — such as “hot-Jupiters” and exoplanets getting blow-torched by their star when they venture too close — astronomers haven’t been able to directly measure the existence of any of these “habitable” exoplanet’s hypothetical atmospheres. Do they even possess atmospheres? Or are they the opposite, with hellish Venus-like pressure-cooker atmospheres? Who knows. Even if they do have atmospheres that are more Earth-like, are the gases they contain toxic to life as we know it?

Recently, theoretical models of exoplanetary atmospheres brought carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide into the discussion. CO2 is a powerful greenhouse gas that helps maintain a balance in our atmosphere, regulating a temperate world (until industrialized humans came along, that is). But too much can be a very bad thing. For exoplanets existing on the outer edge of their habitable zone to remain habitable, they’d need massive concentrations of CO2 to remain temperate — concentrations that would render the atmosphere toxic (to complex lifeforms, at least). In the case of carbon monoxide (the terrible gas that asphyxiates anything with a cardiovascular system), as our star is so hot and bright, its ultraviolet radiation destroys large accumulations of CO in Earth’s atmosphere. But for habitable zone exoplanets that orbit cool red dwarf stars (like Teegarden), huge concentrations of CO may accumulate and snuff-out life before it has the opportunity to evolve beyond a germ. These two factors are a big negative against life as we know it, shrinking the effective habitable zone around certain stars and certain exoplanetary orbits.

Most habitable zone exoplanets have been found orbiting red dwarfs, primarily because our observations have been biased in favor of these little stars — they’re small and cool, meaning that any planet orbiting within their habitable zones need to get up-close and personal, so its an easier task to detect the periodic star wobbles or exoplanetary transits to confirm their existence.

While this may sound cute, orbiting so close to a red dwarf is a blessing (for astronomers) and a curse (for any unfortunate aliens). Many red dwarf stars generate powerful stellar flares that would regularly bombard nearby worlds with radiation that terrestrial biology would not be able to tolerate. Unless those planets have incredibly powerful global magnetic fields to, a) protect their inhabitants from being irradiated and, b) prevent the savage stellar winds from stripping away their protective atmospheres, there’s limited hope for the evolution of life.

Interestingly, however, according to the Teegarden study published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, this particular red dwarf is relatively quiet on the life-killing flare front, so that’s something. Another tentative +1 for Teegarden’s actual habitability! (Pass the tequila.)

As you can tell, there’s lots of exciting implications balanced by plenty of sobering reality checks. There is, however, one factor that is often missed from big announcements about worlds orbiting small stars that, whether they are habitable or not, is truly beyond our experience.

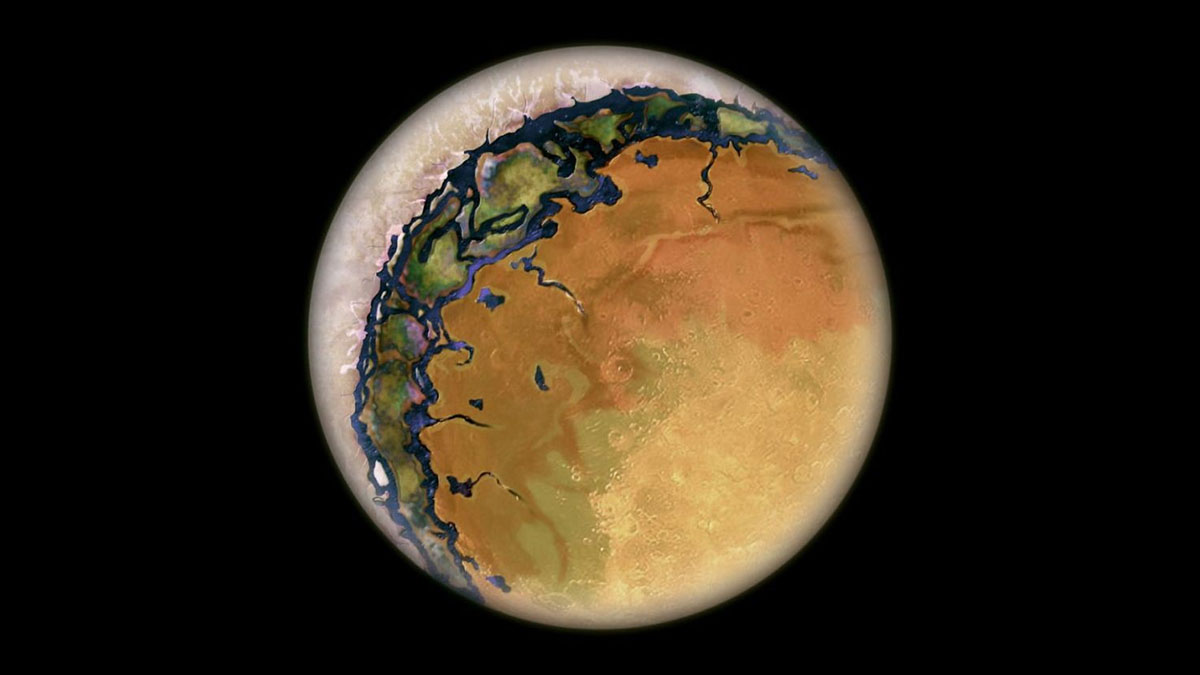

eyeballing temperate red dwarf systems

Teegarden is an eight-billion-year-old star system, approximately twice the age of our solar system. If life has found a way, it will have come and gone, or be in an evolved state (though this is anyone’s guess, we have little idea about the hows and whys of the emergence of life on Earth, let alone on a different planet). But the worlds themselves, if either possess liquid water (Teegarden b, being the one that should be the most temperate of the pair, so will have the higher odds), they certainly wouldn’t look like Earth, even if they have Earth-like qualities.

Having settled billions of years ago, any orbital instabilities would have ebbed, and the planetary orbits would be clearly defined and likely in some kind of resonance with the other bodies in the star system. In addition, both Teegarden b and c will, in all likelihood, be tidally locked with their star.

To understand what this means, we need only look up. When we see our moon, we only see one hemisphere — the “near side”; the lunar “far side” is never in view. Except for the Apollo astronauts, no human has ever seen the moon’s far side with their own eyes. That’s because the moon’s rotation period (28 days) exactly matches its orbital period (28 days) around the Earth. Other examples of tidally-locked systems in the solar system are Pluto and its largest moon Charon, Mars and both its moons Phobos and Diemos, plus a whole host of moons orbiting Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

The same tidal physics applies to red dwarf stars and their closely-orbiting worlds. And Teegarden b and c have very close orbits, zipping around the star once every five and eleven days, respectively, so they are very likely tidally locked, too.

So what does a habitable zone exoplanet orbiting a red dwarf star look like? Enter the “Eyeball Earth” exoplanet:

I’ve written about this hypothetical world before and it fascinates me. As temperate exoplanets orbit red dwarfs so snugly, and if they have an atmosphere, they may too look like the above artistic rendering.

Looking like an eyeball, the star-facing hemisphere of the planet will be perpetually in daylight, whereas the opposite side will be in perpetual night. The near-side will likely be an arid desert, but the far side will be frozen. Computer simulations of the atmospheric dynamics of such a world are fascinating and well worth the read. The upshot, however, is that these worldsmay have dynamic atmospheres where habitability is regulated by powerful winds that blast from the star-facing hemisphere to the night-side, transporting water vapor in a surprisingly complex manner. These worlds will never be fully-habitable, but they may host in interesting array of biological opportunities nonetheless.

For example, there may be a “ring ocean” that separates the desert from the ice, where, on one side, tributaries flow into the hot hemisphere only to be evaporated by the incessant solar heating. The vapor is then transported anti-star-ward, only to be deposited as it freezes on the night-side. One could imagine this massive buildup of ice on the planets night-side as an hemisphere-wide glacier that slowly creeps sun-ward, where it melts and pools into a temperate ring ocean where the process starts all over again.

Like Earth, the atmospheric dynamics would need to be balanced perfectly and if an alien ecosystem manages to get a foothold, perhaps such a planet-wide “water cycle” could be sustained while maintaining the life that thrives within.

hypothetically habitable

So, whenever we hear about the latest exoplanetary discovery, and take note that these strange new worlds are “Earth-like” or “habitable,” it’s worth remembering that neither may be accurate. Sure, finding an Earth-sized world in orbit around their star in the habitable zone is a great place to start, but it’s just that, a start. What about its atmosphere? Does it have the right blend of atmospheric gases? Is it toxic? Does it even have an atmosphere? Whether or not an alien world has a global magnetic field could make or break its habitable potential. Does its star have sporadic temper tantrums, dousing any local planets with a terrible radiation storm?

These challenges are no stranger to the astronomers who find these worlds and speculate on their astrobiological potential, but in the excitement that proceeds the discovery of “Earth-like” and “habitable” exoplanets, the headlines are often blind to the mechanics of what really makes a world habitable. The next step will be to directly observe the atmospheres of habitable exoplanets, a feat that may be within reach when NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) go online.

The fact is, we know of only ONE habitable world, all the others are hypothetically habitable — so let’s look after this one while it can still sustain the rich and diverse ecosystem we all too often take for granted.

[ this article was originally published on astroengine.com ]