why science says we should be spending a lot less time at the office

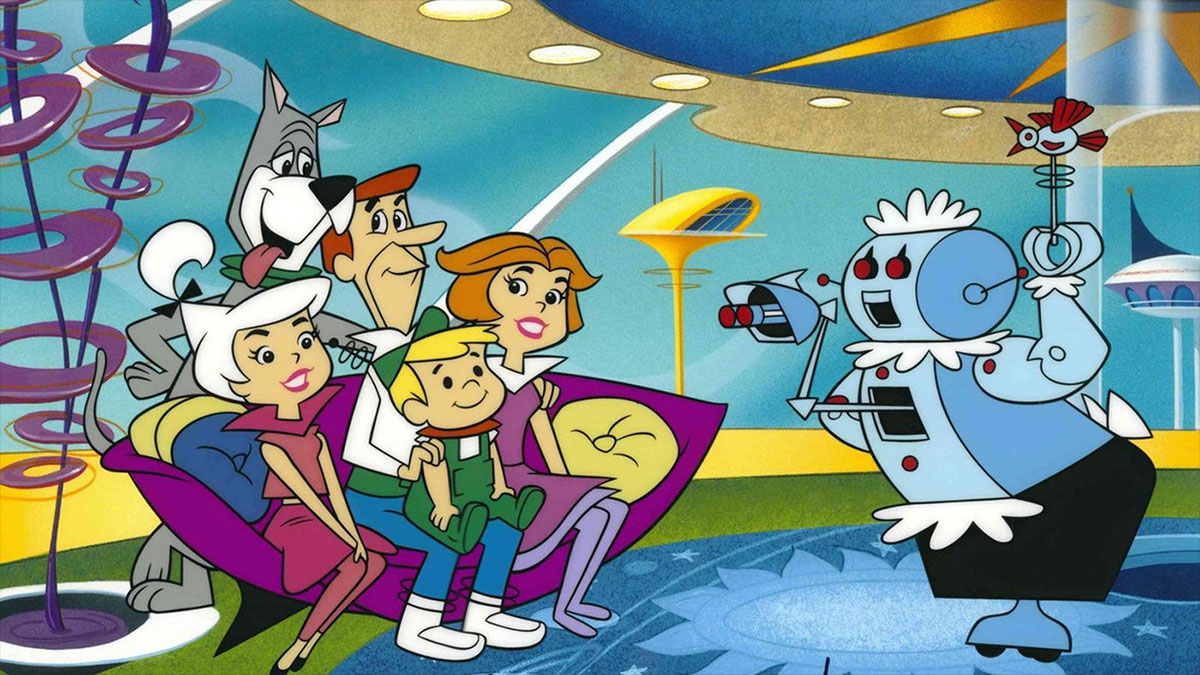

Back in the middle of the past century, influenced by science fiction and post-war utopianism, much of the Western world believed that these days, we’d all effectively be part timers as ever more sophisticated machines take over more and more routine, boring, dangerous labor while we use our vast downtime to create art, volunteer, come up with new ideas, and just enjoy life. In The Jetsons, a four hour work day was referred to as brutal because at the time, numerous employers and legislators explored very popular efforts to keep shrinking the hours we spent at the office. But instead, as we all now know, we’ve been chaining ourselves to the office more and more, creating a full blown Soviet-style cult of overwork for the sake of overwork.

You can probably hear the angry murmuring of bosses and business owners about the perils of not working with the same cliches we’ve heard for the past two centuries. After all, we managed to build entire societies around the idea that work, no matter how useful or necessary, should be the sole arbiter of a person’s worth. Numerous robber barons and politicians have told us very explicitly that we should view those who work fewer hours or earn less money as lesser people whose situation must be a result of their moral failings. But since so many of them believe that we should be working for them until we physically collapse from exhaustion, asking their opinion on shorter work weeks is often like asking foxes’ opinions on stronger chicken coops.

Nevertheless, a number of organizations started doing experiments and asking researchers if the assumptions which drove the creation of the current work week hold up today. How many hours in the office are optimal? How many days a week are really best allocated to work? This isn’t just an exercise in being nice to employees for the sake of being nice. Anyone who worked in white collar jobs will tell you how much time and effort is wasted with pointless meetings and status reports or idle chatter, so compressing work days is just as much of an effort to focus on quality of work and eliminate waste. The results? Those in jobs requiring creativity and deep focus function best with four work days lasting five hours, or half of today’s norm.

how did we arrive at a 20 hour work week?

This number comes from two primary ideas to reduce time at work by optimizing efficiency, the first is a four day work week and the other is a five hour day. An extra day off gives people a bit more room to breathe and put out domestic fires or figure out their chores so they don’t have to carry over to the office. You can schedule a convenient visit from a handyman instead of trying to set one up at work and take time off to wait for one to come, or pop out of a Zoom meeting when they arrive. Instead, you’re focussed on work instead of what household emergencies you have to handle, and on your chores without worrying about attending a meeting. You would also prioritize truly important tasks since you have less time to work on them.

Other experiments asked for how long we can be steadily focused and productive, and the answer is about four hours. Given that number, some companies tried asking workers to get as much done as possible in five hours and see what happens. The end result was a similar drive to eliminate time wasters like status meetings, pointless reports, internet browsing, and IM chats with co-workers to prioritize tasks and get them knocked out as quickly and well as possible. In return, all this hyperfocus and prioritization was rewarded with time off, a powerful incentive that really motivated workers to get stuff done. Knowing that when you’re done around 1 pm you can just go home is a fantastic motivator.

And that is the critical component in all this. People don’t want to live to work, they’re very aware they’ve traded time they’ll never get back to do work they don’t enjoy two thirds of the time. Why bother getting everything done in four hours when they’ll just be slammed with more loathsome work from a boss who thinks they run a widget factory, when you’re trapped at the inefficient and probably disease-riddled office for at least eight? This is why, as observed by Cyril Parkinson, work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion. Narrow the time and you can, as paradoxical as it sounds at first, increase the work done by forcing workers to cut out the fluff, filler, and coping rituals developed to deal with the pressures of the office rat race.

so, why are we working and wasting so much?

Now, if you have a certain type of boss, you’re probably reading this and thinking “oh no, if they read this, they’re going to think that if what currently takes 40 hours can be done in 20, we’re all getting dragged into an all hands meeting to be called lazy and have our work doubled!” This is, of course, the exact wrong message to take from this information. It’s not that humans are able to hyperfocus in four hour bursts, it’s that four hours a day is where you’ll get peak performance and you’ll just be hitting diminishing returns afterward. If you do away with every single little time waster at the office and force your subordinates to go for the standard eight to ten hours, you’ll simply burn them out.

But there’s still a very large group of managers and business owners who are only capable of judging performance by presence in an office with devastating impacts on company morale and future opportunities. If you were to sit them down and explain that time at work doesn’t mean time working, and that quantity of work doesn’t mean usefulness of work, they will look at you with hollow, glassy eyes and intone “but they’re at the office!” And if you explain that our minds come up with the best ideas during downtime, they’ll react as if you relieved yourself over their relatives’ graves. People like this are still in charge of the vast majority of workplaces around the world, despite their leadership coming at great cost to society, especially in times of crisis.

And that’s why you’re not going to see 20 hour work weeks anytime soon. In societies which worship work for the sake of work, reducing time in the office or on call from home is seen as antithetical to the overall mission of the enterprise. Certainly there are businesses where deep focus is unnecessary and these numbers may not necessarily make sense, but they should be targets for more automation, freeing up more people to do creative, diverse work with minimal meetings and interruptions, without overtaxing them and letting them live their daily lives. If we really want another productivity revolution and ease the burning political tensions, the status quo is simply not sustainable, and the sooner we do something about it, the better.