when, why, and how popular science lies to you

Over the last two years or so, it seems like the world separated into two camps: those who think science is an important tool for making key decisions about our present and future, and those who’d rather watch YouTube videos about how The Queen of England is actually an alien lizard from Tau Ceti that eats human flesh. But while science is both good and very important, and we have to keep learning about it to navigate the modern world in case something like, oh, I don’t know, a pandemic requiring basic scientific literacy to effectively combat hits us, we also need to keep in mind that not all science is equally certain or accurate in its conclusions. Some fields are just plain more reliable than others for reasons often out of scientists’ control.

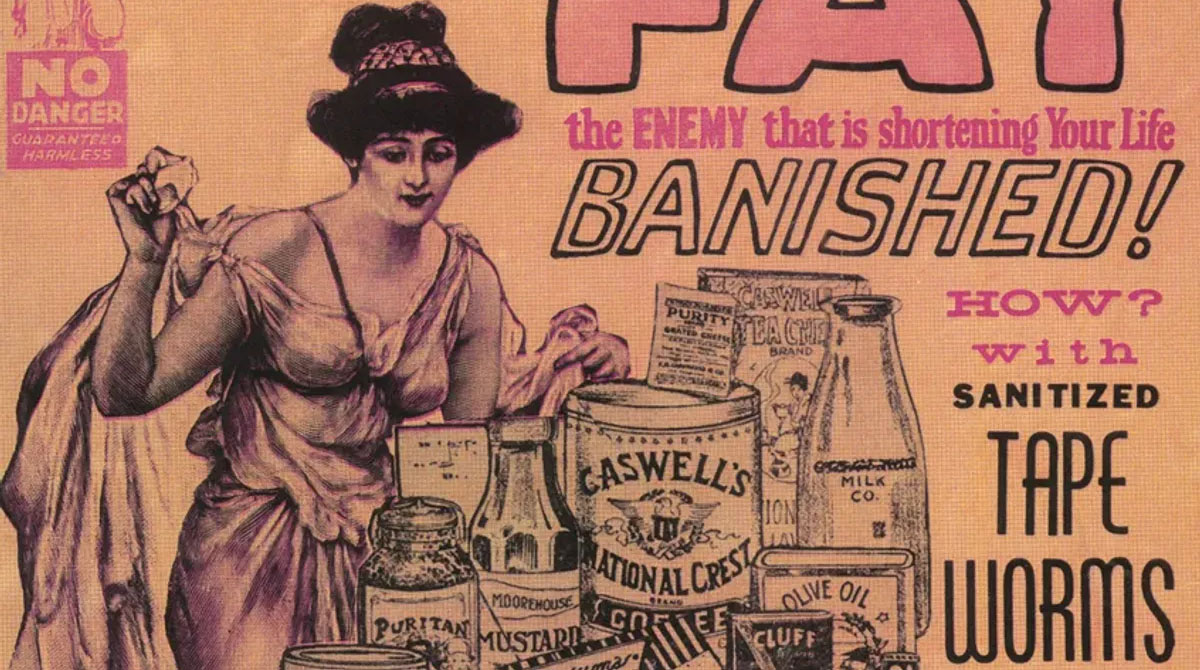

Nowhere is this more true than in the fields of social sciences and health, the sources of many catchy pop science headlines about how wine will either give you a heart attack or help your circulation, how tea will either give you cancer or cure it, and how many orgasms you should have per year to add a certain number of months to your lifespan. Without them, Dr. Oz’s entire media career would not exist — at a net benefit to humanity, one might add — and neither would dozens of sites that specialize in making you feel clever for remembering scientific-sounding trivia. In the end, we end up woefully misinformed and asking whether skipping breakfast will give you heart disease because freelance writers paid a pittance needed some clickbait.

For an example, consider studies showing that having extra heft, and habitually drinking alcohol and coffee will shorten your lifespan while another set of studies say the exact opposite. All the data may be correct and show exactly what the researchers claim, but that prompts the question of how those studies could come to the exact opposite conclusions. The answer? They probably studied different groups of people. If the first set tracked the health of those scientists politely refer to as socioeconomically disadvantaged, the subjects would very likely be in worse shape and live shorter lives in the first place, especially in nations where they would have significant financial barriers to decent healthcare.

In this case, coffee intake wouldn’t matter all that much, alcohol could be a coping mechanism, and extra weight a sign of a poor diet rich in processed foods, consumed on the go between jobs or due to the higher cost of healthier alternatives. Meanwhile, wealthier subjects may drink plenty of coffee and booze, and pack on a few extra kilograms, but live long, healthy lives because they’re farther from sources of pollution, get better medical care, eat healthier, and have the time and resources to engage in activities that prolong and improve one’s life. What those studies set out to answer was whether coffee and alcohol had an impact on our health, and if so, what it was and how significant. But that’s not what they found.

What they ended up finding were symptoms of class divide with coffee, alcohol, and BMI as partial proxies. Researchers are, of course, aware of this and the fact that studying real living, breathing people is extremely complicated and definitive results require an extreme level of control that too many labs lack the funds and approvals to do. They don’t set out to ignore the complexities of being a person when doing their experiments and studies, but in order for their studies to get anywhere, they need to focus on very narrow, concrete questions. Unfortunately, this approach, combined with the obsession of publication counts and citations by those who grant scientists tenure and funding, backfires badly when used in bad faith.

Just consider the latest kerfuffle with Dan Ariely, a scientist studying dishonesty and how to fight it, caught being less than honest with data used in one of his landmark papers. Or a lab whose work on food habits and weight loss was routinely promoted on daytime talk shows and in viral pop sci articles blatantly and aggressively manipulating data to arrive at conclusions meant to get media attention, not useful, factual advice. Or the decades-long crusade by a single scientist to defund and blackball any researcher who raised the alarm about the amount of sugar in our diets solely because his studies blaming fatty foods as the source of all obesity brought him fame and cash with which he wasn’t willing to part.

Now, the point here isn’t that science is wrong and you should just pick whatever belief aligns with your personal opinions. No, the point is that how studies are done is important and when you hear catchy headlines with loud flashy numbers about topics as complex as weight loss, cancer risks, the effect of mild vices on your heart and brain, or matters of social psychology, you should be skeptical. Just like with salespeople or strangers on the corner in windowless vans promising candy and piles of cash to anyone who’ll get inside with them, if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is, and it was published to get someone a publicity boost and extra funding because it catches your attention.

But, of course, science does have a major perk when it comes to dealing with these claims. It’s a self-correcting process. Individual researchers may deceive themselves or commit fraud, but sooner or later, someone will try to replicate their studies, fail miserably, go over their data, and catch the error or lie. This is why we know about all the aforementioned cases and why there are numerous critiques of bad studies across the web. Criticizing and questioning is, after all, what scientists do, and if you look at a trendy pop sci factoid spreading across the web, shake your head and start asking hard questions about sample sizes, sources of funding, and whether the authors’ own words match the quoted result, you’re just thinking like a scientist.