the universe’s axis of evil and why the cosmos is askew

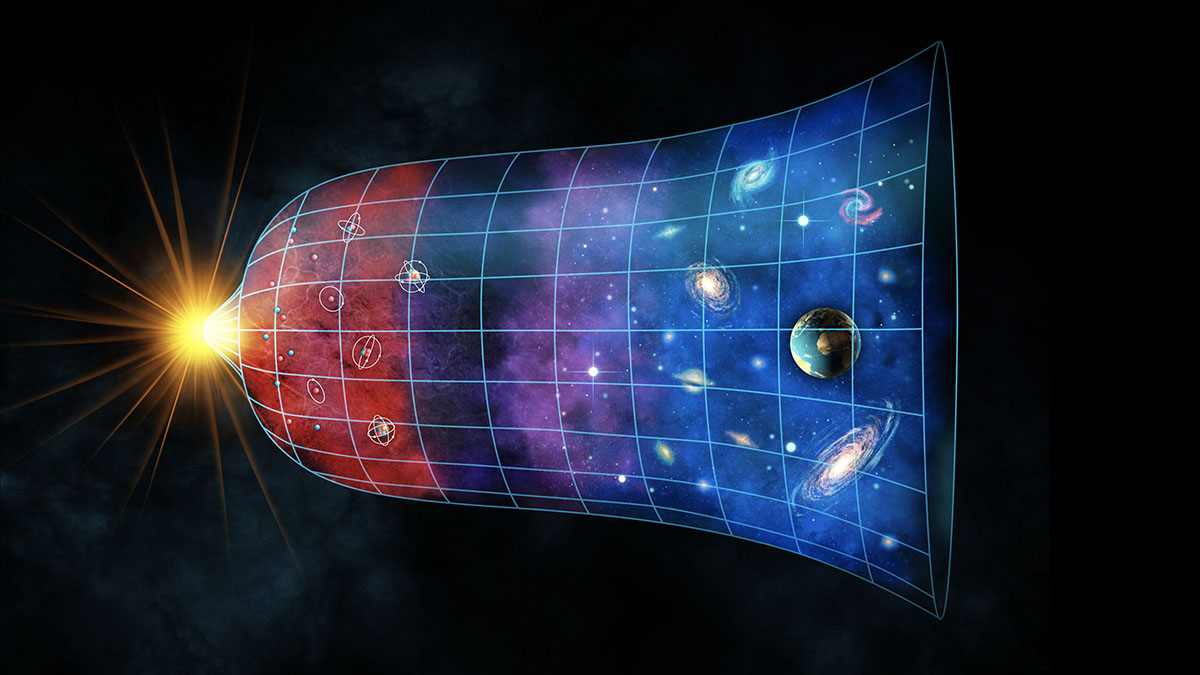

According to the cosmological principle, our universe is isotropic and homogeneous on the largest possible scales, which is a very fancy way of saying that if you zoom out far enough, all of existence looks pretty much the same and no place in it is unique. If you were to travel to the original site of the Big Bang, if that was actually possible, you’d find absolutely nothing special about it. This apparently uniform shape of the universe dictates a certain set of physical and temporal laws which can be used to understand the cosmos and our place in it.

But what if I were to tell you that current research looking at hundreds of galaxy clusters and plotting them against the plane of our solar system found that the universe may actually be lopsided, with some parts of it further away and dimmer than current models would predict, while others are closer and brighter? We’d need a new word in our vocabulary: anisotropic. And we may also need some new laws of physics to explain why the cosmos doesn’t behave like we thought it should given what we know.

We could argue, as many cosmologists have, that we can’t possibly see all of the universe, so the disparity could be accounted for on even greater scales still out of our reach. We could also say that the data is anomalous because small errors projected across billions of light years can give a distorted picture and we just need to keep measuring. But the problem is that we did in fact keep measuring, and the asymmetry just isn’t going away. In fact, we just keep discovering strange currents and bubbles real and imagined as we probe deeper and deeper.

This is such a frustrating problem that the plane of our solar system showing the anisotropy was called “the axis of evil” in the first paper to prominently raise attention to these findings. While it may not affect the typical Newtonian physics of planetary life, or have any bearing on general or special relativity of deep space, it could force us to rethink concepts like dark matter and energy, inflation, and the fate of our universe over deep time, forcing us to question our best hypotheses trying to understand phenomena we’re still unable to fully explain.

So, what do these findings tell us? Simply put, that we don’t know enough about the universe and it would be foolish to pretend otherwise. It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be teaching students about the Big Bang, or inflation, or any of the many things on which we appear to have a grip because they are true, and they do seem to be the best explanations we have for what we see and measure today. But it does mean that we need to open some more room for questions and skepticism about putting all those pieces together into a comprehensive narrative.

We still don’t know exactly what the Big Bang was, so what banged, where, and how, are just mathematical guesses right now. We know there were signs of massive events that shaped the first stars and galaxies, and created the filaments that hold the universe together. But we don’t know the full size and shape of the universe, why it moves the way it does, or how it will end, and it’s important to honestly say that we don’t know, rather than shoehorn in an idea with which we feel comfortable.

It’s also important to acknowledge that for many people, the unknown, especially the kind of unknown that calls into question their very existence, is profoundly disturbing and jarring, and knowing that we’re still struggling with a comprehensive picture of the cosmos and its laws and future. A lot of humans need structure, purpose, and a definition, a sort of checklist to living life without too many uncomfortable questions, to the point where they’re driven to totalitarian and destructive ideologies. Telling them more things we don’t know will only lead to anger.

What’s the answer? We need to be a lot more comfortable with not knowing, and not in that shrug-our-shoulders-and-move-on way, but that I-don’t-know-but-let’s-find-out way which is the attitude that underlies the scientific method. Our civilization, and really, any civilization if we think of it, can only prosper when we make it our mission to explore, grow, and find out, not sit around and make up busywork, fretting over imaginary problems and enemies because we’re bored out of our minds. There’s a whole universe out there to discover. Let’s do that instead.