why scientists want to grow a tiny version of you in a petri dish

When a company called Renewal Bio demonstrated the ability to grow mouse embryos in an artificial womb, the big question was what’s next. Now, we have an answer. Growing early-stage human embryos which can’t develop past six weeks, then use their stem cells to 3D print organs and tissues for the donors from whom they were effectively cloned. As you can imagine, this idea is raising a lot of very concerned eyebrows and prompting a lot of awkward and scary questions, which, to be fair, are warranted.

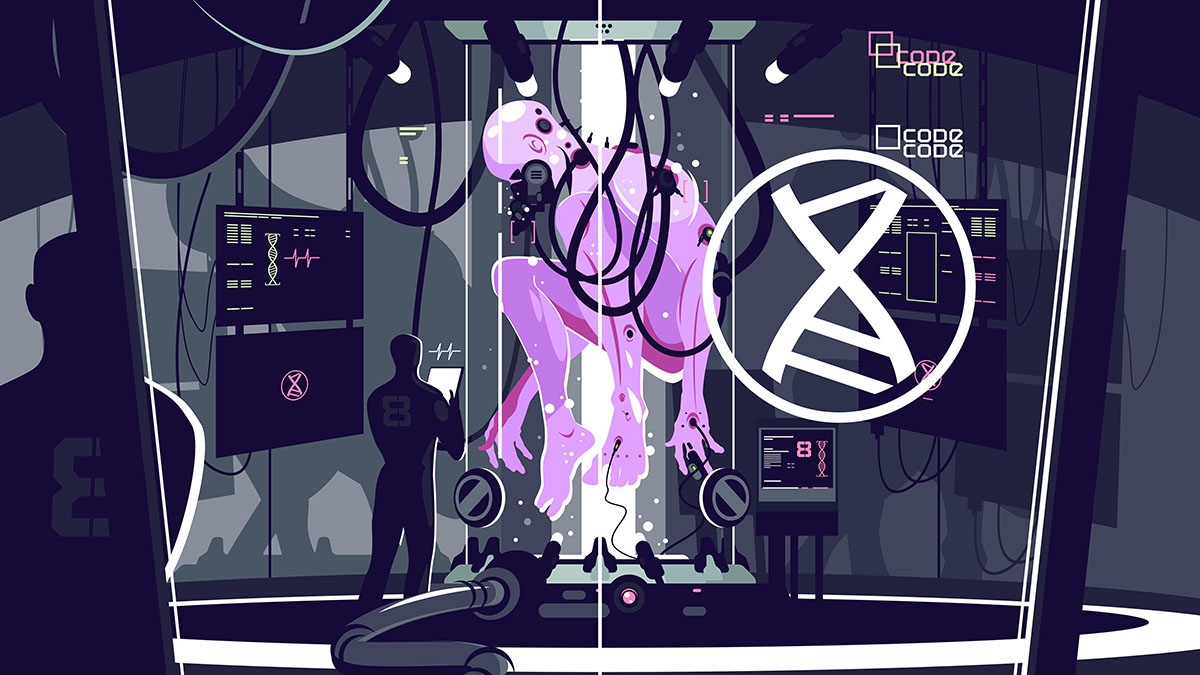

If you’re thinking that this sounds an awful lot like the plot of numerous sci-fi properties where the hapless protagonists learn they are just clones grown for harvesting a variety of spare parts, you’re sort of correct. But because this is the real world and biology is a lot more complicated than that, you would be wrong if you think that Renewal is seriously suggesting creating some sort of nightmarish dystopian organ farm. A successful end result would look like a warehouse full of bioreactors producing structures and organic factories for organs to 3D print.

While it’s apparently now possible to create an embryo purely out of stem cells, without sperm or eggs, and there are experimental artificial wombs meant to help bring fetuses to term, there is a biological bridge there. Viable development requires a uterus and umbilical cord. Without them, stem cell embryos are simply not viable, eventually developing abnormalities that shut down all function inside them, much less qualify to finish gestation in an artificial womb. Your stem cell clone will never mature into a human, just a set of differentiated organ templates.

It’s those organ templates that Renewal is after. You see, while there have been strides in 3D printing human organs from stem cells, the end products are currently incomplete or too small for transplantation and use. In a 40-to-50-day embryo, however, there’s enough differentiation and structural integrity to extract and grow the organ to a size that could be actually useful in medicine. If successful, this method would save tens of thousands, and allow patients to enjoy their new lives without anti-rejection drugs that have to drastically lower their immunity.

Or, at least, that’s the goal provided these stem cells don’t go rogue inside patients’ bodies as some stem cells have been known to do for reasons we’re still trying to fully understand. And even if everything works exactly as hoped, you can see why millions of activists would bitterly oppose this technique, unable and unwilling to grasp the fact that the embryos in question can never develop into humans. The imagery and idea behind the process would simply be far too shocking and unnerving for them to ever accept.

Much like the technology that now allows us to reanimate dead brains, this is a case of science moving much faster than our current ability to handle what it’s showing us. Of course, we want research to keep moving at a steady pace, especially when there are lives to save. But in some cases, we need to be ready to tackle the tricky moral questions, implications, and yes, the ick factor of certain projects before we commit more resources to them. To paraphrase a classic movie quote, in cases like the Renewal proposal, we should really take the time to think about whether we should do something than whether we can.